How Screen-Time Limits Fail and What Matters More

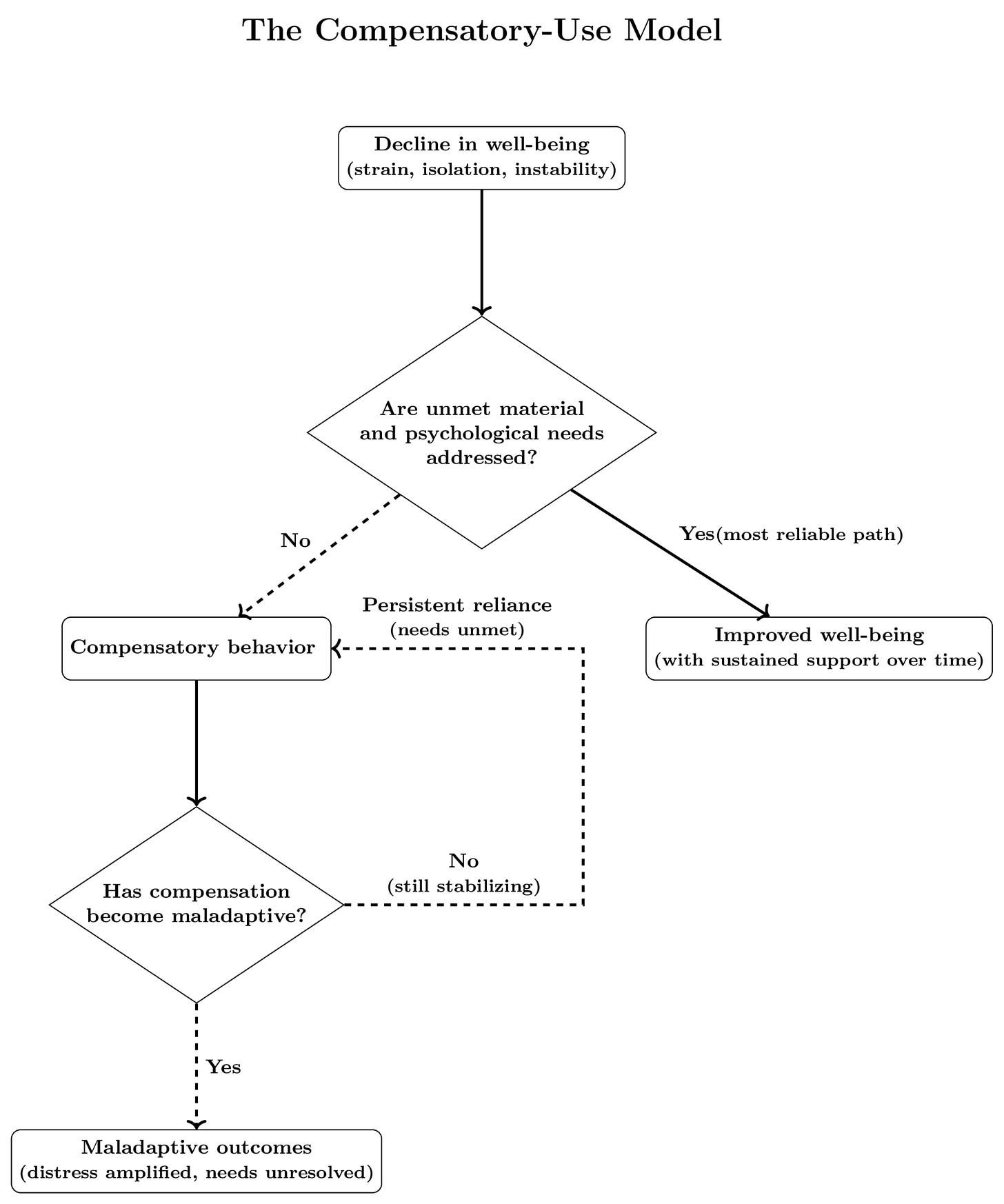

Introducing The Compensatory-Use Model

The modern debate over youth mental health has settled on a familiar explanation. Smartphones and social media are said to be addictive, to crowd out real life, and to leave young people anxious, lonely, and depressed. If that account were sufficient, the remedy would be obvious. Restrict access, and well-being should recover.

Yet the groups most likely to face strict limits are not the ones that see the largest gains from them.

When we look closely at the data, a different picture emerges. Phones do matter, but their role is often misunderstood. Instead of operating as a primary source of distress, heavy phone use appears to function as a compensatory behavior. When young people lack reliable sources of support or connection, they turn to tools that provide stimulation or regulation. Heavy screen use fills gaps left by unmet material and psychological needs.

This essay develops what I call the compensatory-use model. The figures that follow draw on Monitoring the Future survey data from 2021 to 2024, the years in which parental screen-time limits were explicitly expanded to include social media.

Who Is Able to Impose Limits

Discussions of screen-time rules usually begin with whether they work. A more basic question comes first. Who is actually in a position to enforce them?

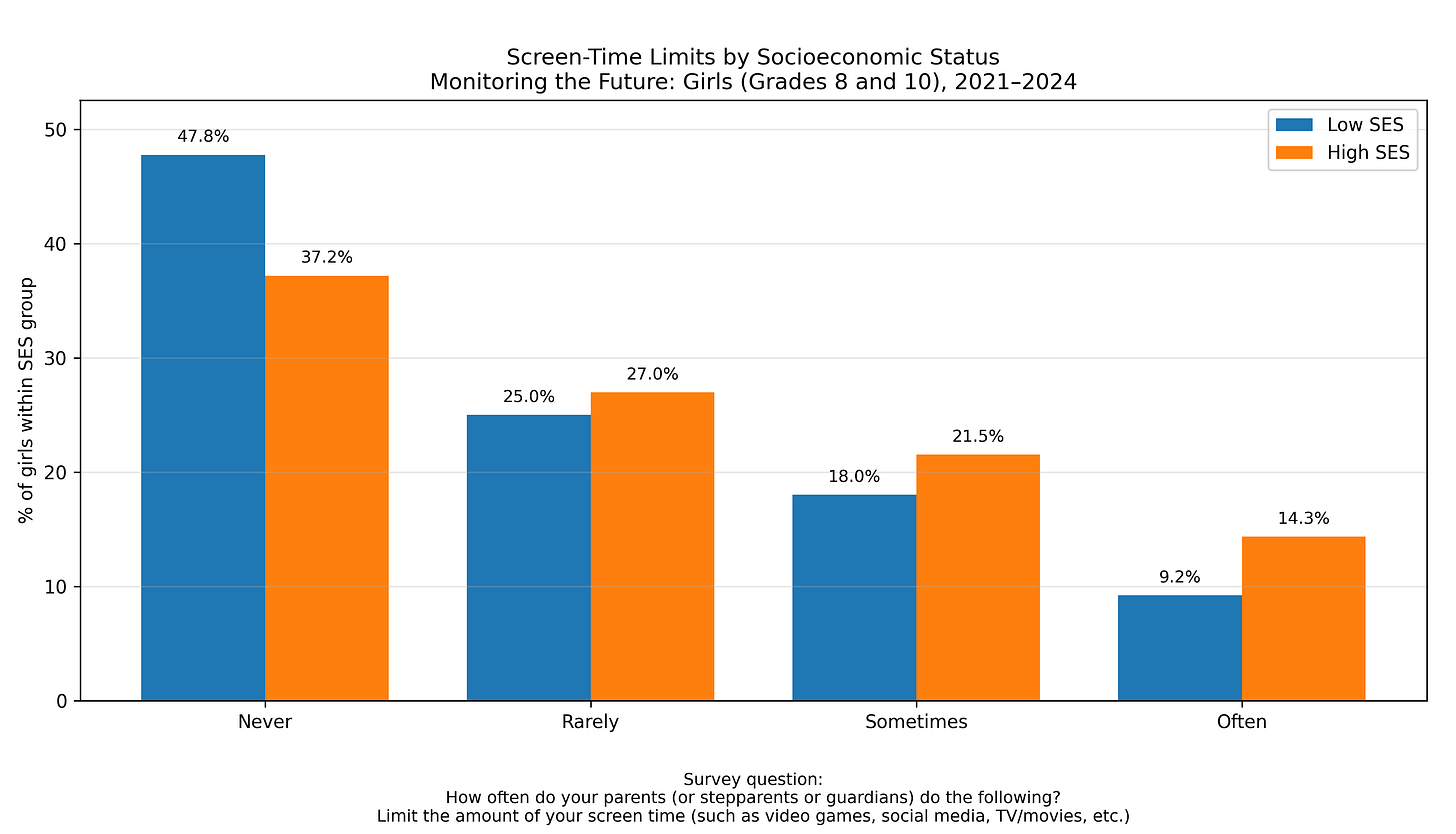

Figure A shows that enforcement itself is socially patterned. Nearly half of girls from lower socioeconomic households report that limits are never enforced, compared with just over a third of girls from higher socioeconomic households.1 Frequent enforcement is noticeably more common among higher socioeconomic families.

These differences reflect ordinary constraints. The exhaustion produced by competing responsibilities while trying to make ends meet shapes what parents can realistically monitor and sustain. Screen-time rules are not evenly available levers. They sit downstream of material conditions that vary sharply across households.

When access rules are treated as a universal intervention, that asymmetry disappears from view. Restrictions narrow a tool without addressing the circumstances that made the tool useful in the first place.

Who Has Reliable Parental Support

Even where limits are feasible, many proposals assume dependable access to parental guidance when problems arise.

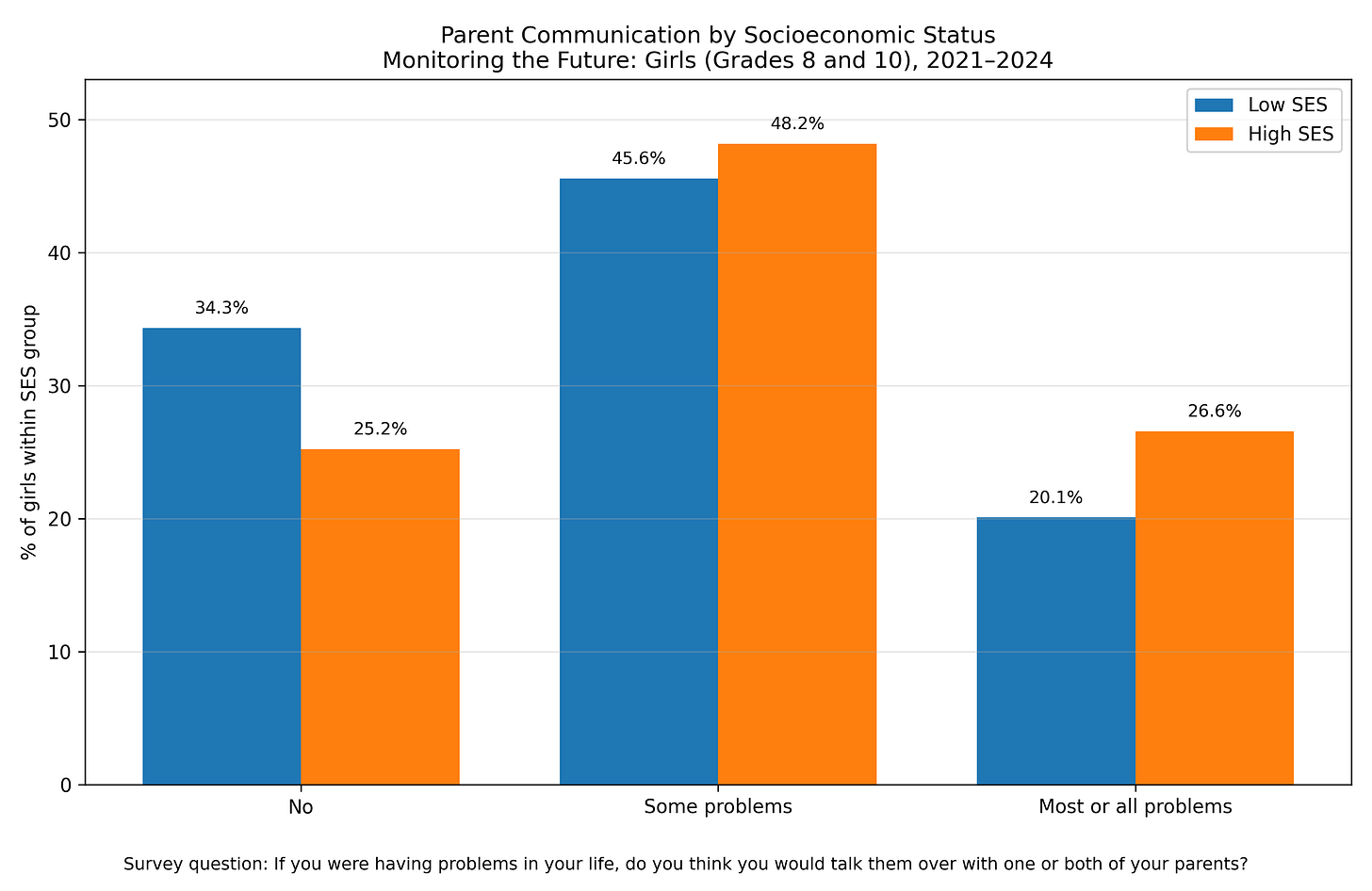

Figure B shows responses to the question: if girls were having problems in their lives, would they talk them over with one or both parents?

The distribution reveals a quiet divide. Roughly one-third of lower socioeconomic girls say they would not talk to a parent about their problems, compared with about one-quarter of higher socioeconomic girls. Higher socioeconomic girls are substantially more likely to report talking with parents about most or all problems.

The middle category, talking about some problems, looks similar across groups. The divergence appears at the edges. Lower socioeconomic girls are more likely to be fully outside the communication system. Higher socioeconomic girls are more likely to be securely inside it.

Parental communication is shaped by the same pressures that shape enforcement. Stress and competing demands affect not only rule-setting but conversation itself. Limits presuppose conversational capacity. They do not operate independently of it.

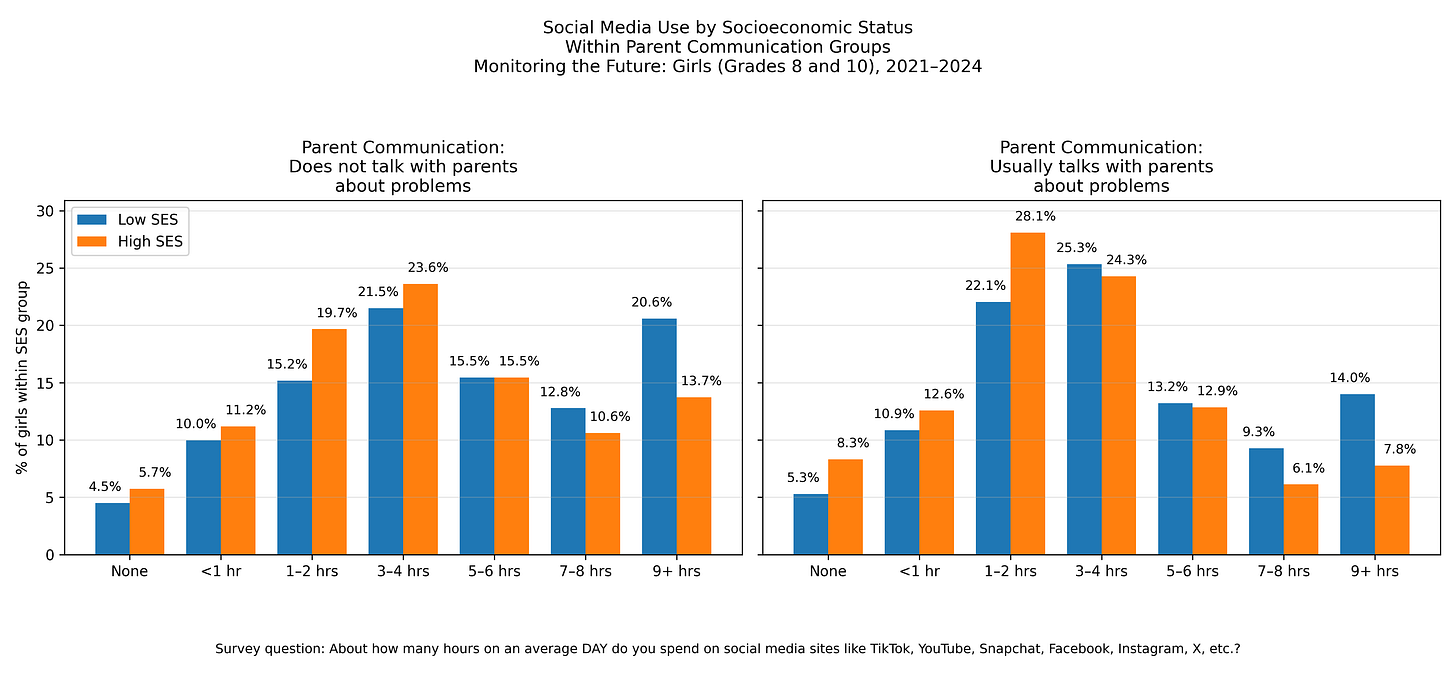

Who Uses Phones the Most

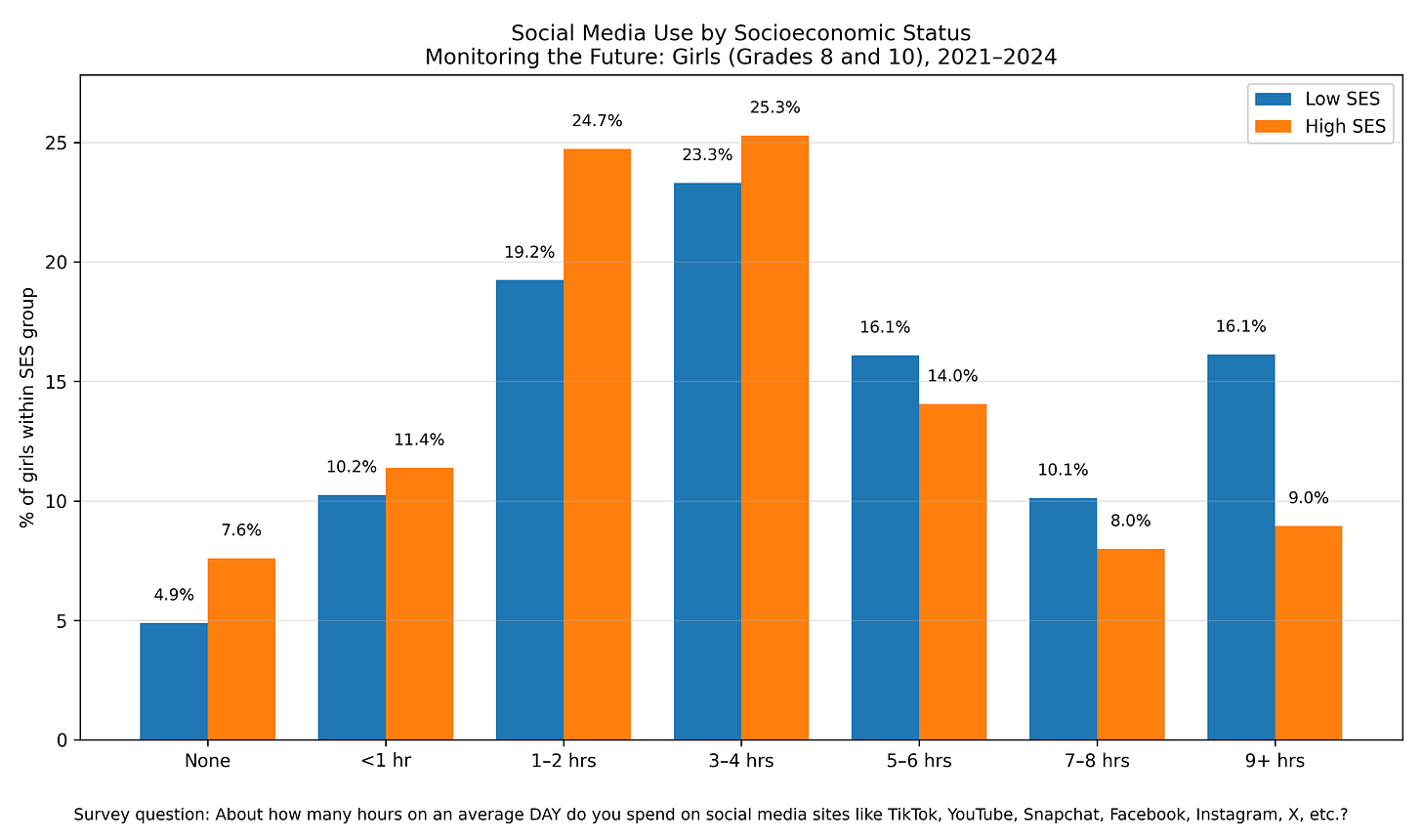

If access to support is uneven, those differences should show up not only in reported well-being but in everyday behavior.

Figure C shows that they do. Girls from lower socioeconomic households are disproportionately represented in the highest social media use categories. Five or more hours per day, seven to eight hours, and nine-plus hours are all more common among lower socioeconomic girls. Higher socioeconomic girls cluster more heavily in lower and moderate use ranges.

This pattern appears before any claims about harm are made. Screen time here signals exposure to constraint. High use reflects limited alternatives, not parental indifference.

Figure C-1 sharpens the picture. When social media use is examined within parent–child communication groups, a consistent gradient emerges. Within both socioeconomic strata, girls who usually talk with parents about their problems spend less time on social media and are less likely to appear at the extreme end of the distribution. Where communication is absent, use shifts upward.

Communication does not eliminate socioeconomic differences, but it reliably reduces reliance on social media within each group. Use declines because the need for compensation is lower, not because access is forcibly constrained.

These patterns help explain why heavy phone use so often correlates with distress. The association is real, but its direction is commonly assumed instead of demonstrated. Unmanaged use may aggravate distress at the margins. The more consequential question is whether use is initiating distress or intensifying conditions that already exist.

If phones were the primary driver, restricting them should produce clear and consistent gains, especially among those with the highest use and lowest well-being.

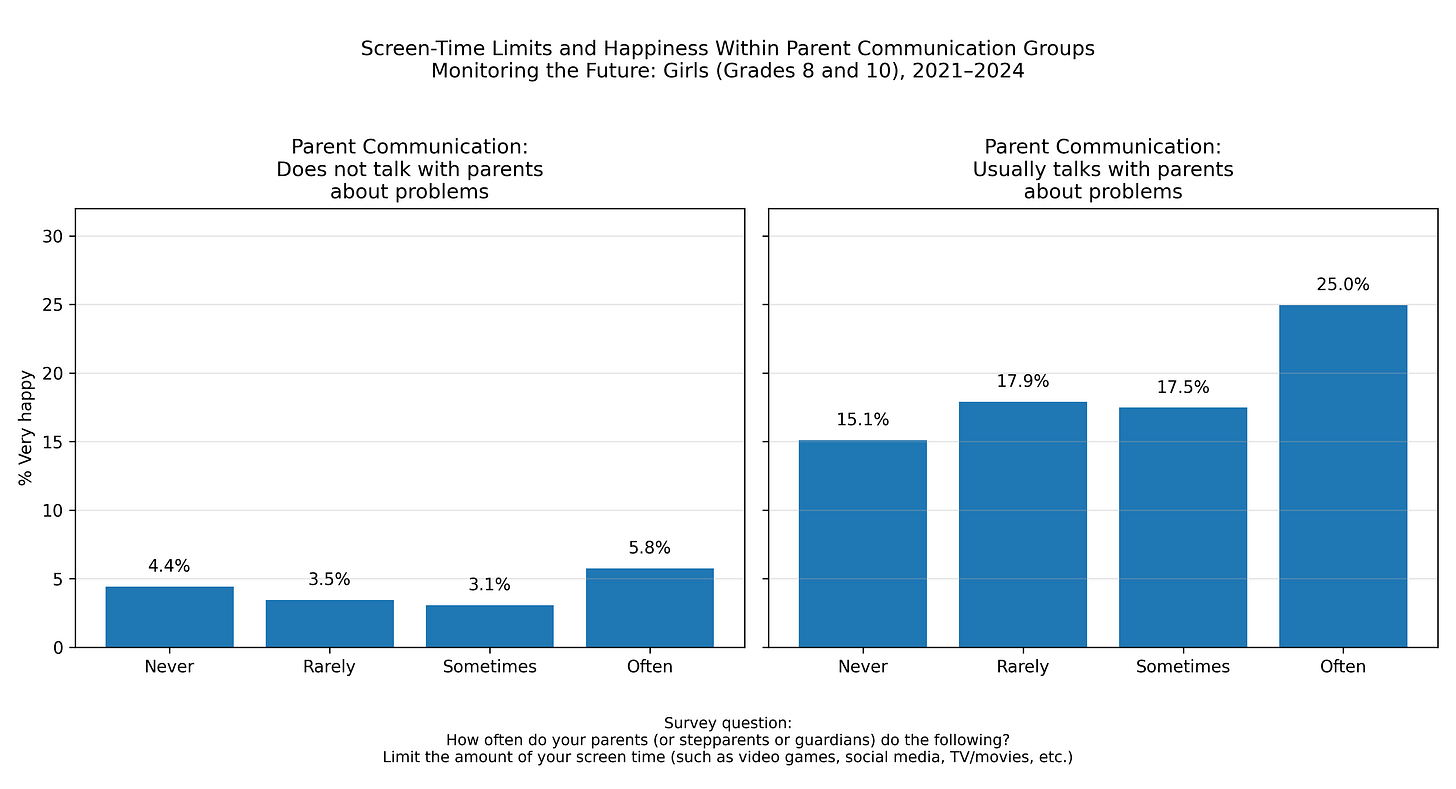

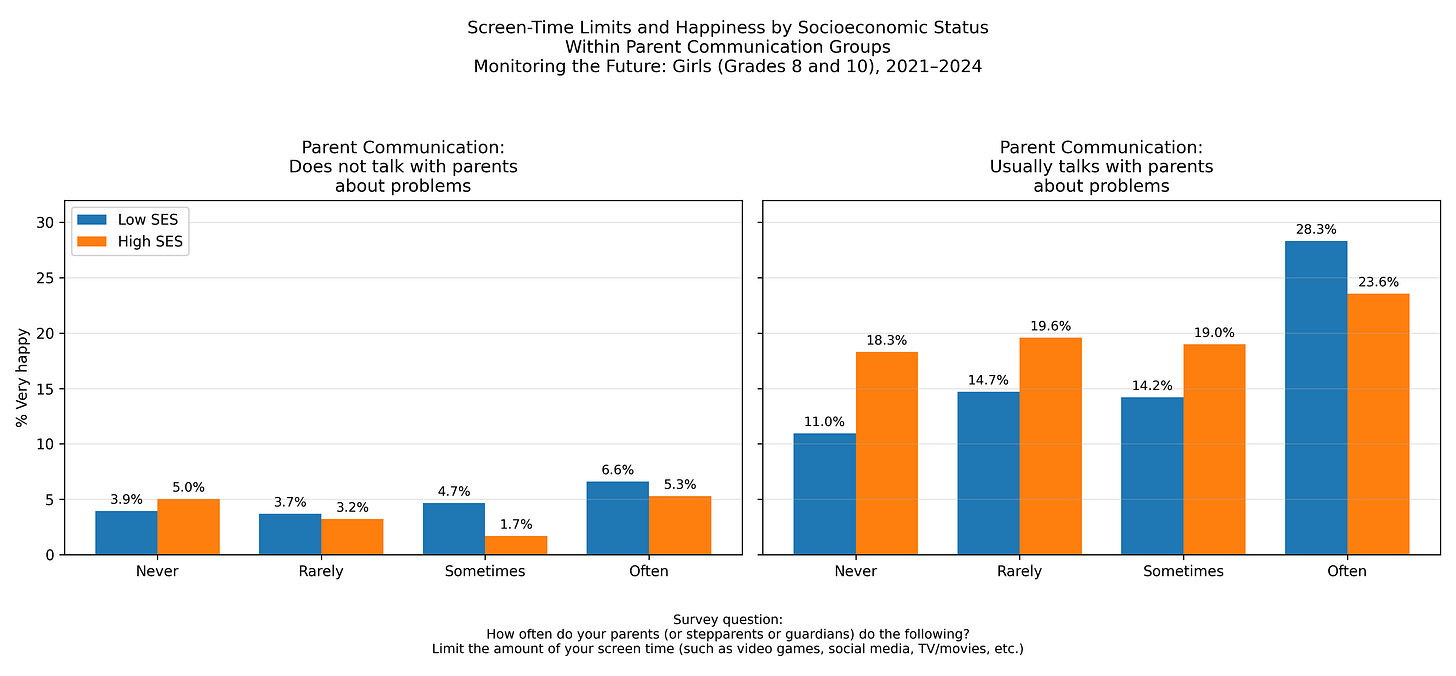

Why Limits Fall Short

Figure D examines that claim directly by comparing girls within the same parent–child communication environments.

Among girls who do not talk with their parents about problems, happiness remains low regardless of how often screen-time limits are enforced. Whether limits are never imposed or imposed frequently, outcomes change little.

A modest association appears only among girls who report talking with parents about most or all problems. Within that group, frequent limits are associated with slightly higher happiness. The size of this difference is small compared with the effect of communication itself.

Figure D-1 extends this comparison across socioeconomic status. The same conditional pattern holds for girls from both lower and higher socioeconomic households. Where parent-child communication is absent, limits show no meaningful association with happiness at any socioeconomic level. Where communication is strong, frequent limits are associated with somewhat higher happiness for both groups.

Limits therefore do not appear to repair harm on their own. They function within contexts where dependable relational support is already present. In those settings, rules likely signal parental involvement, including reliability and attentive responsiveness to a child’s specific needs.

Where those relational conditions are absent, limits do not substitute for them. Restricting access addresses neither the unmet needs nor the circumstances that made the tool attractive. In strained or isolated contexts, removal can intensify distress by cutting off one of the few available sources of stimulation or regulation.

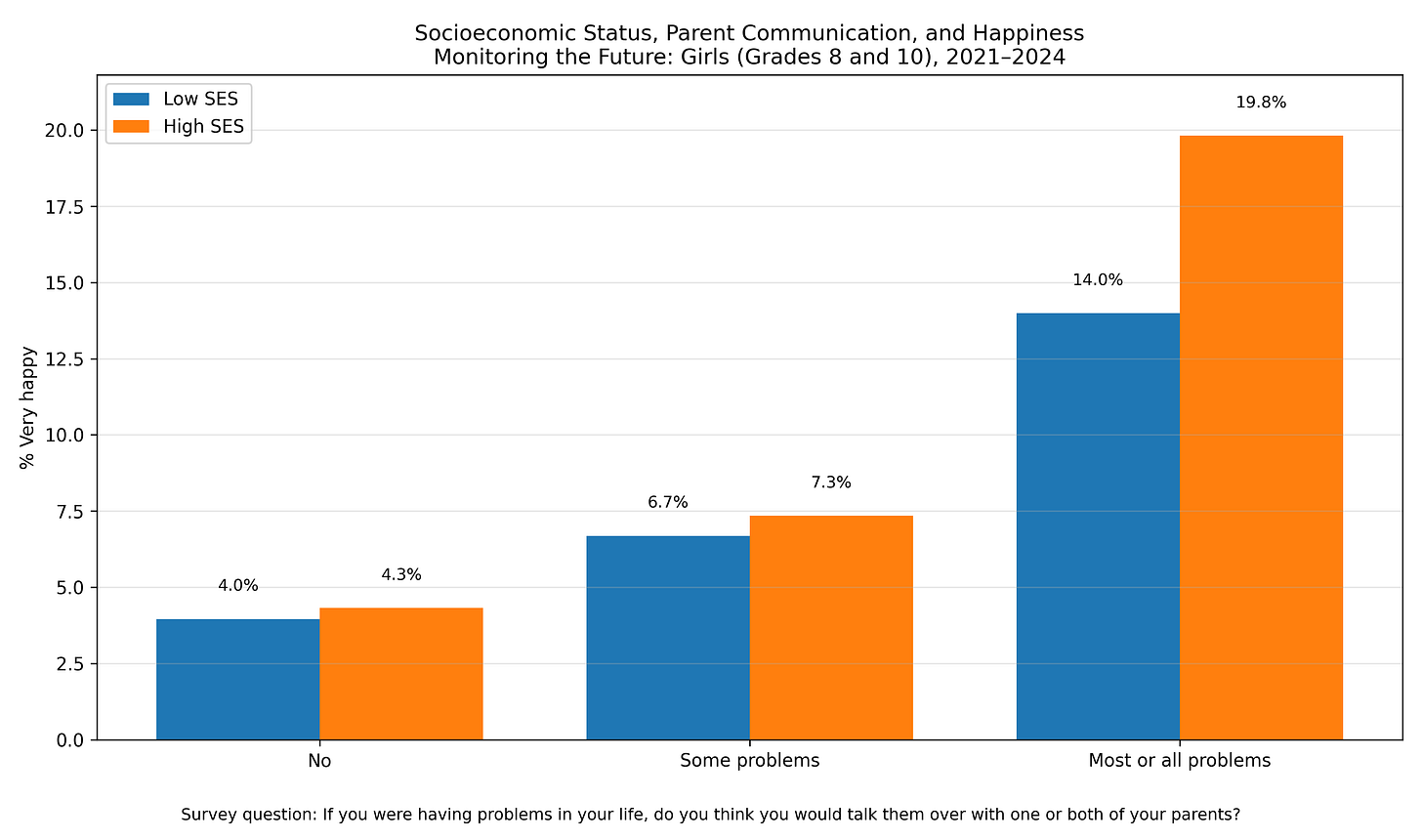

Why Relationship Outweighs Resources

If limits matter only conditionally, the next question is what most consistently explains differences in happiness across households.

Figure E shows a steep and ordered gradient by parent–child communication. Girls who report no communication are rarely very happy, regardless of socioeconomic status. Those who report talking about some problems fare better. The largest gains appear among those who report talking about most or all problems.

Occasional communication helps, but it does not close the gap. Dependable access to parental support is where well-being rises most sharply and where socioeconomic differences narrow.

Material resources still matter. Higher socioeconomic girls are, on average, somewhat more likely to report being very happy. When communication is absent, that advantage largely disappears. When communication is strong, its protective effect is substantial for girls from both socioeconomic groups. Lower socioeconomic girls with strong communication often report higher happiness than higher socioeconomic girls without it.

Resources can ease stress and expand options. They do not substitute for sustained, attentive involvement. Economic strain shapes how easy those conditions are to maintain, not how important they are.

A Combined Test

A statistical model was used to examine these relationships simultaneously by predicting the likelihood that a girl reports being very happy.2

The model includes socioeconomic status, parent–child communication, screen-time limits, and an interaction between limits and communication.

The results reinforce the patterns in the figures. Parent–child communication dominates the model. Girls who report strong communication are about three to four times more likely to report being very happy than those who report none. Socioeconomic status shows a smaller independent association. Screen-time limits contribute little on their own and matter modestly only when strong communication is already present.

If phones were the central problem, limits would emerge as a robust solution across contexts. They do not.

Scope and Implications

This argument does not claim that smartphones and social media are harmless. Heavy, unmanaged use can disrupt sleep, amplify social comparison, and expose vulnerable young people to content that worsens anxiety or mood. In some circumstances, especially where use is extreme, limits may reduce additional harm.

Nor does the model dismiss the value of rules or routines. Clear boundaries can be stabilizing when embedded in warm, attentive relationships. The findings are consistent with that role.

What the compensatory-use model rejects is a stronger claim. It rejects the idea that smartphone exposure itself is the primary driver of youth distress and that prohibition is therefore the central remedy. If that causal story were correct, limits would show large and consistent benefits across households, including among those with the weakest communication and highest distress. They do not.

Figure F traces the underlying logic. When material and psychological needs are addressed upstream through sustained support, well-being improves over time. When those needs remain unmet, young people turn to compensatory behaviors. These behaviors can provide temporary relief, but when they become persistent substitutes for support, they often grow maladaptive and deepen distress. Interventions that focus only on downstream behaviors treat the symptom instead of the cause and rarely produce durable change.

Digital technologies are general-purpose tools whose effects depend heavily on context. They are not analogous to intrinsically harmful products like cigarettes, nor are restrictions on them comparable to safety interventions that operate independently of family conditions.

That is why broad legal restrictions are unlikely to deliver uniform benefits and why rigid household rules so often disappoint. When a technology functions as compensation, removal does not address the reason for its use. In some cases, it exacerbates the underlying strain.

The most reliable way to improve youth well-being is to meet individual needs through connection instead of control.

That work depends on cooperation, not compliance.

Socioeconomic status in this analysis is proxied by maternal education. Households in which a mother has a college degree are classified as higher socioeconomic status, and those without as lower socioeconomic status. The choice of this SES proxy and the focus on girls in grades 8 and 10 follow prior uses of these survey items in analyses of Monitoring the Future data, most notably by Jean Twenge. Using the same items allows the patterns examined here to be evaluated on comparable footing, while the analytic emphasis differs.

Binary logistic regression using Monitoring the Future data for girls in grades 8 and 10 from 2021 to 2024 shows that parent–child communication has the largest association with reported happiness. Girls reporting strong communication are much more likely to report being “very happy” (OR ≈ 3.4, 95% CI ≈ 2.4–5.0; d ≈ 0.70). Screen-time limits show little independent association (OR ≈ 1.0), with only small conditional effects in high-communication households (OR ≈ 1.2; d ≈ 0.10–0.15). Socioeconomic status shows a modest association (OR ≈ 1.25; d ≈ 0.15) but is far less predictive than parent–child communication.

Great points. Is this study published?

Re moderate internet use, here's the latest: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/article-abstract/2843720?widget=personalizedcontent&previousarticle=2839941#