An Economic Explanation for the Youth Mental Health Crisis (Abridged)

Note: This post is an abridged version of my first post.

Introduction

The Smartphone and Social Media Theory (SSMT) is the most popular explanation for the youth mental health crisis because it offers an easy answer to a complex problem. It advocates for the prohibition of smartphone and social media use among young people due to the correlation between increased screen time and the decline in teen mental health. However, when economic conditions are taken into account, it becomes clear that SSMT reverses the direction of causation—increased screen time is a symptom, not the cause, of declining mental health.

The Root Cause

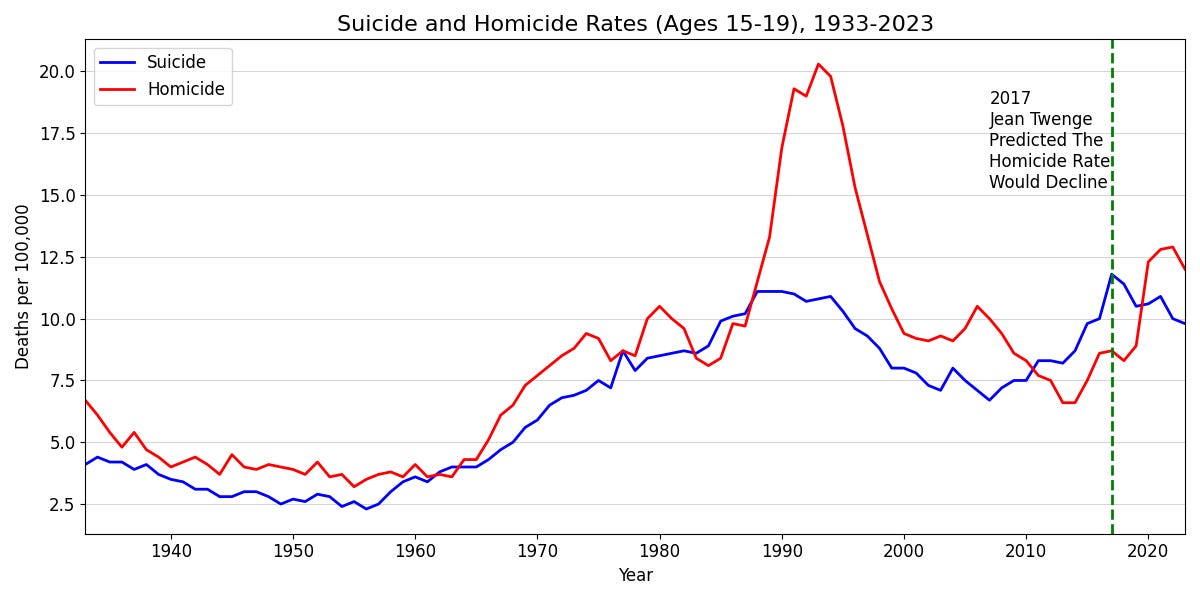

In her 2017 book iGen, SSMT proponent Jean Twenge predicted that youth homicide and suicide rates would diverge—suicide increasing and homicide decreasing—due to the rise in isolation and loneliness caused by smartphones and social media. However, this prediction never came to fruition and likely never will because, as Figure 1 shows, youth homicide and suicide rates have been correlated since the U.S. government began officially tracking this data for all states in 1933.

The fundamental flaw of SSMT is that it cannot explain the correlation between youth homicide and suicide. The correlation between the two suggests that they are two sides of the same coin.

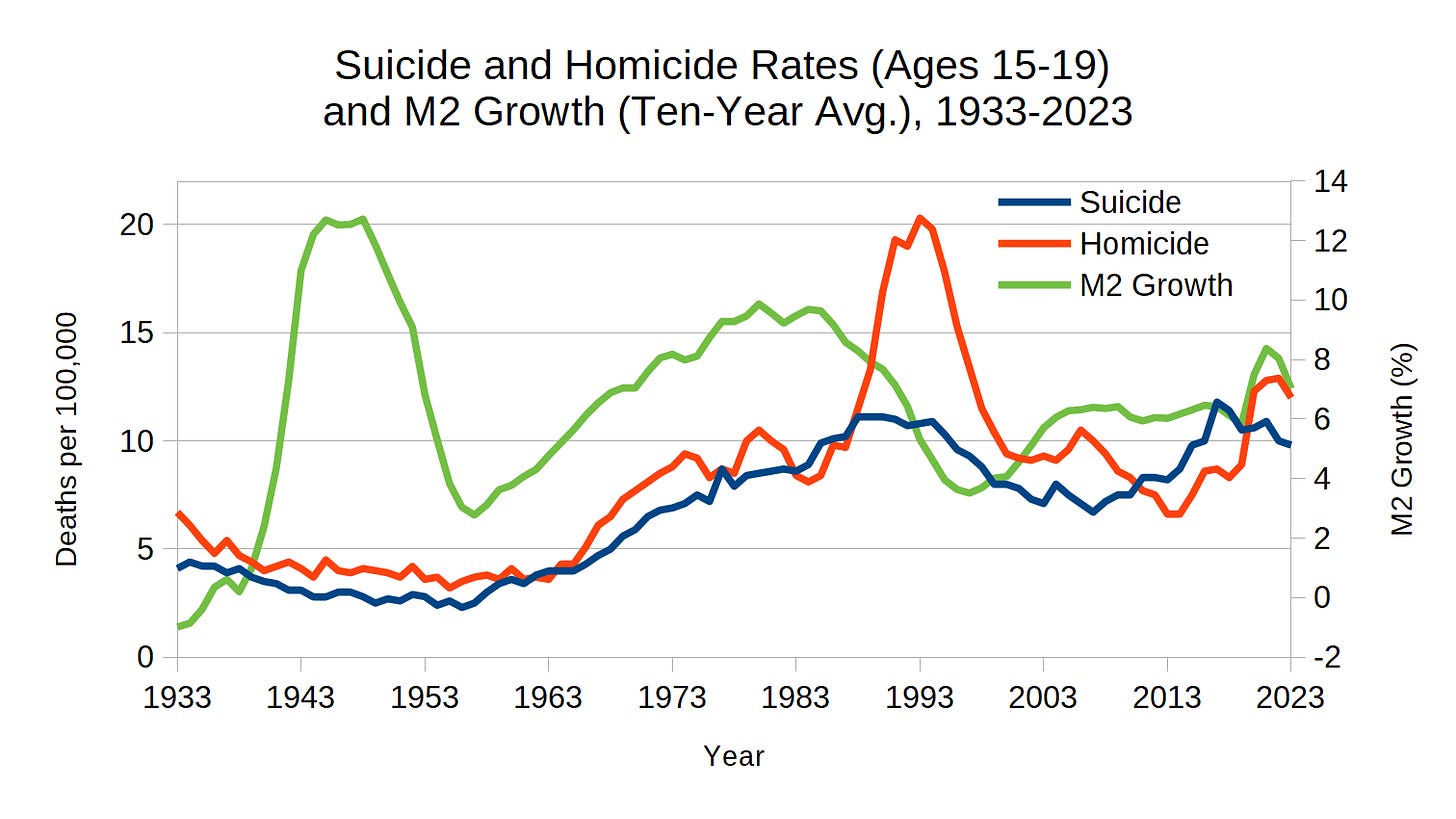

Researcher Meyer Harvey Brenner found that economic instability and insecurity caused by economic cycles are associated with both homicide and suicide rates. According to the Austrian Business Cycle Theory (ABCT), economic cycles are driven by increases in the money supply. By synthesizing Brenner’s findings with ABCT, we can see the connection between suicide, homicide, and the money supply. Figure 2 presents the homicide and suicide rates for individuals aged 15 to 19 alongside the ten-year moving average of M2 money supply growth (M2 growth).

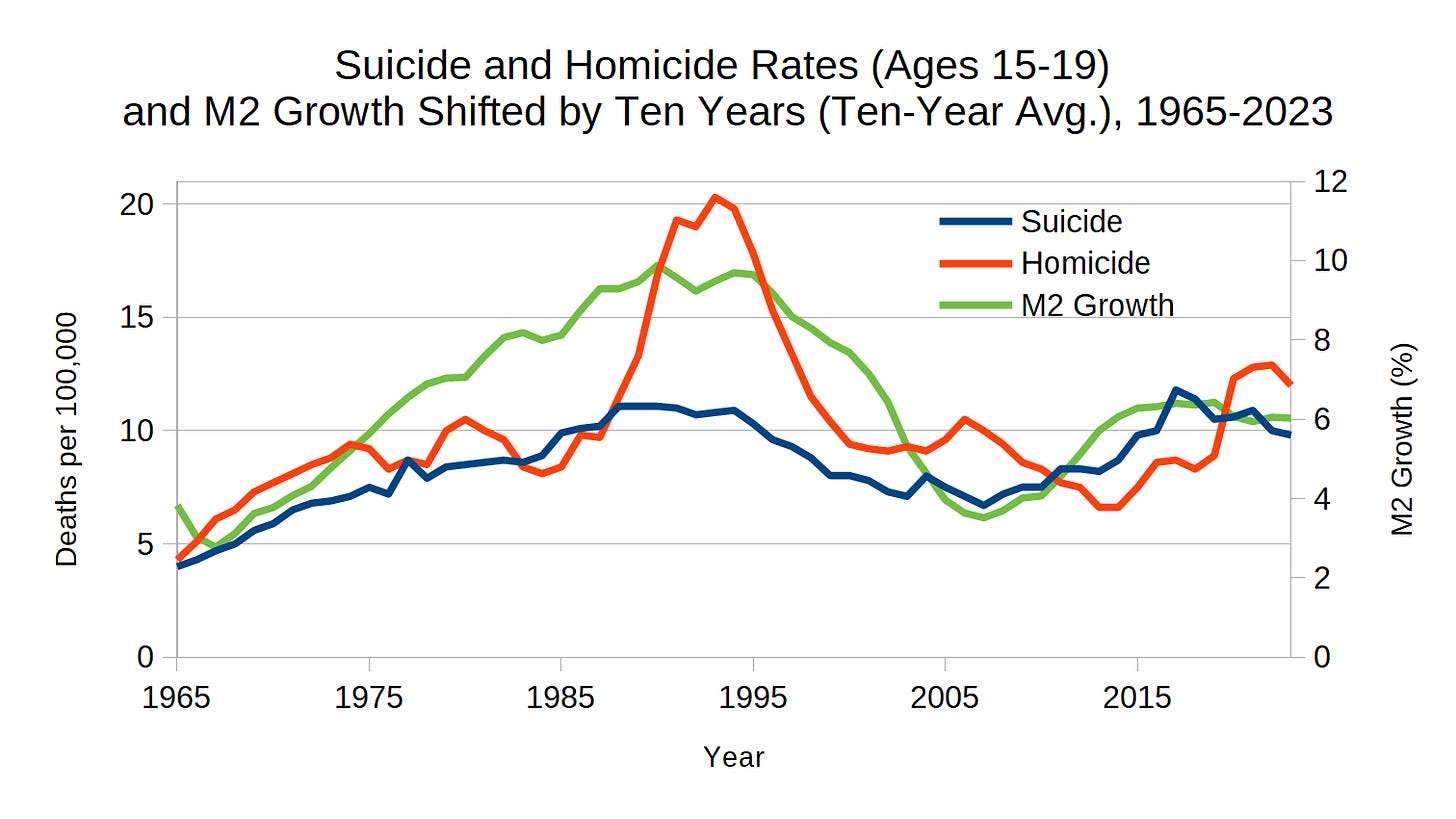

Due to a lag, shifting M2 growth makes the correlation more apparent, as shown in Figure 3.

Two of the three M2 money supply waves between 1933 and 2023 align with the two waves of suicide and homicide rates. The first M2 money supply wave did not impact suicide or homicide rates during World War II, likely due to two primary factors. The first was low unemployment, which alleviated a significant aspect of financial stress for many. The second was a unifying sense of purpose—defeating the enemy. This collective mission gave Americans a reason to accept many of the negative consequences of the war at home, such as price inflation and internment camps. During this time, individuals focused on survival and service over personal struggles.

This appears to be what’s happening. A significant increase in the money supply, which often leads to economic instability and insecurity, creates widespread distress. For some, this distress impacts mental health so severely that they die by suicide. In other cases, it manifests as frustration and anger, sometimes culminating in violence. Based on the data, young people seem especially vulnerable to the distress caused by increases in the money supply. I refer to this particular type of distress as easy money-induced distress and my explanation as Easy Money Distress Theory (EMDT).

Symptoms of Easy Money

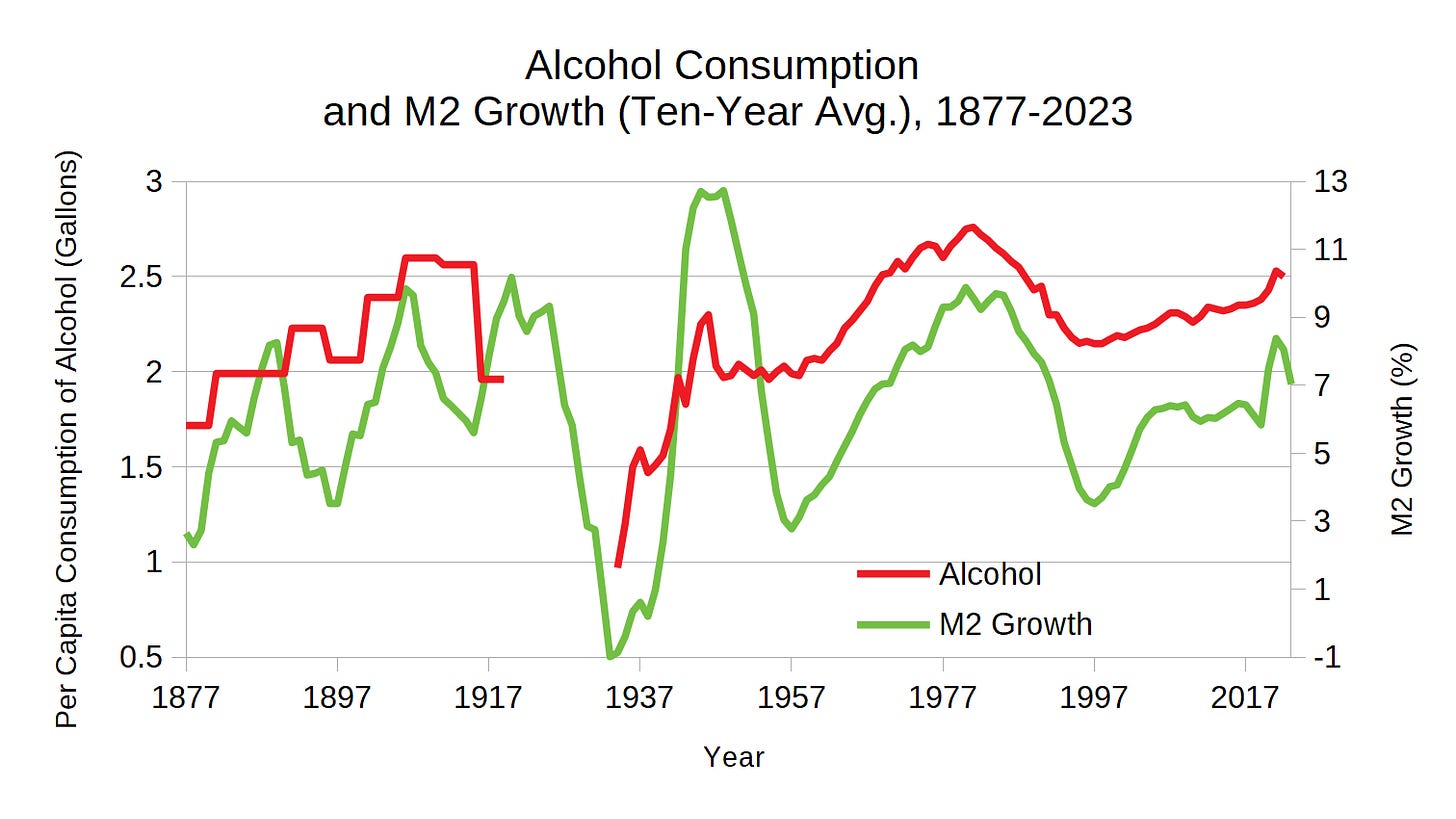

Many individuals develop coping mechanisms to deal with this distress. For example, when we plot alcohol consumption alongside M2 growth, as shown in Figure 4, the correlation suggests that alcohol is used to soothe easy money-induced distress.

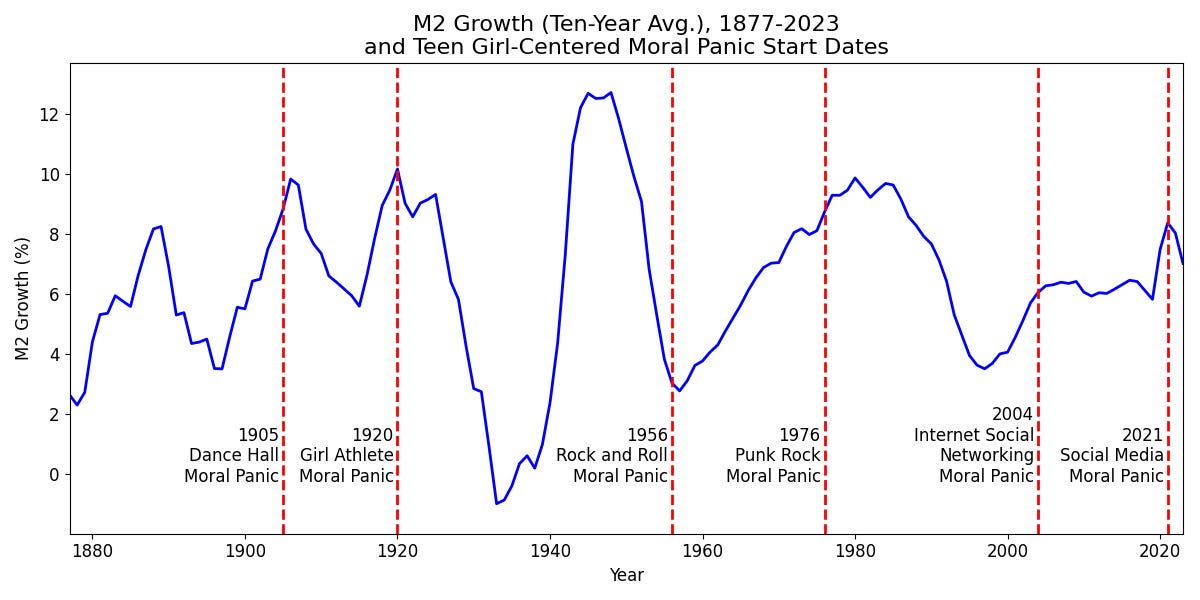

Another way we cope with easy money-induced distress is by establishing a sense of certainty through scapegoating. Figure 5 shows the timing of past moral panics centered around teen girls alongside M2 growth. Since our current moral panic also revolves around teen girls, I have included it as well, marking its start in 2021—the year social media executives were called to testify before the Senate.

Young people are affected in many ways, but for simplicity, I will focus on just one. A growing number of parents, concerned about their children’s economic future, are adopting a parenting style known as intensive parenting. This approach prioritizes academic achievement to ensure children are prepared for an increasingly precarious economy. However, many parents may not realize that this strategy often comes at the expense of their child’s psychological well-being.

Figure 6 shows that the rise of intensive parenting was followed by an increase in academic stress, both of which surged after the 2008 financial crisis.

To understand what young people attribute academic stress to, we can look at research on college students. According to the Cleveland Clinic, teenagers and college students often face similar stressors. In their book The Real World of College, Howard Gardner and Wendy Fischman investigated mental health distress on college campuses. They found that academic pressure was the leading cause of distress, but the primary source of that pressure was not the workload itself—it was the emphasis on “achieving external measures of success.”

This finding is understandable, as young people are increasingly encouraged, from an early age, to view school as their job and to participate in activities that build their résumés. As a result, they often become preoccupied with meeting the externally imposed expectations of their parents and society—at the expense of their basic psychological needs. To cope, many turn to their screens.

Psychologists Richard Ryan and Edward Deci, who developed Self-Determination Theory, describe this phenomenon as the need density hypothesis. In the book Indistractable by Nir Eyal, Ryan explains, “The more you’re not getting needs satisfied in life, reciprocally, the more you’re going to get them satisfied in virtual realities.”

A Closer Look at Screen Time

SSMT’s demands for smartphone and social media prohibitions are unwarranted because they address the symptom rather than the root cause of youth distress. To be clear, I am not saying that screen time doesn’t matter—parents’ concerns about the content their child can access online are justified. However, as danah boyd and Mike Masnick argue, reducing risk isn’t about eliminating it entirely; it’s about preparing individuals to face challenges effectively.

For example, learning to cross a street involves risk, but when parents teach their child how to cross safely, the potential for harm decreases significantly. Similarly, determining when a child is ready to cross alone shouldn’t be based on an arbitrary age but rather on their readiness and a parent’s judgment.

boyd was the first to recognize how calls for technology prohibitions often stem from conflating risk with inevitable harm—a mistake we might term the prohibitionist fallacy. Rather than prohibiting smartphones and social media, a more reasonable approach is to help young people become competent at managing online risks.

A young person’s social media use doesn’t have to follow an all-or nothing approach—it can be gradual. Learning to use social media can be seen as similar to learning how to ride a bicycle, which often begins with training wheels and parental guidance. As young people become more competent, parents can gradually grant more independence. Just as a young person gains the skills to explore the physical world independently on their bike, they can also be ready to explore the digital world—guided by the same gradual approach. Young people can enjoy the benefits of any technology—whether it’s a bike or a smartphone—while mitigating potential downsides.

The primary solution to the widespread distress we are witnessing is a sound monetary system, but parents don’t have to wait for government action to help their children. They can prepare their kids for the future while also ensuring that their psychological needs are met. According to Self-Determination Theory, these fundamental needs are autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Autonomy means having control over one’s actions, competence is feeling capable, and relatedness involves feeling connected to others.

Conclusion

SSMT posits that increased screen time leads to a decline in mental health. However, as we’ve seen, the reality is the other way around. People with declining mental health who aren’t having their basic psychological needs met spend more time on their devices as a way to cope with easy money-induced distress.

Like SSMT, my theory is also based on correlation, but unlike SSMT, it can predict both youth homicide and suicide rates. As long as the government continues to implement easy money policies, youth homicide and suicide rates will generally follow the growth of the money supply.

Interesting theory. But note how before you added the ten-year lag, it actually appeared to be an INVERSE correlation between M2 money supply and distress contemporaneously. That would dovetail more with Rodger Malcolm Mitchell's theory of Monetary Sovereignty, namely, that recessions are caused by shrinking or reduced growth in money supply (and prosperity by increased growth in money supply, as a growing economy requires a growing supply of money), while inflations are caused by shortages of goods and services, not by growth in the money supply. So I would argue, from the principle of parsimony, that you are correct in the "it's the economy, stupid!" explanation, albeit in the opposite direction, and that you are still correct nonetheless that smartphones and social media are NOT the central casual factor here.

One more thing I would like to add: it is probably more a question not of how much the M2 money increases, but rather WHO does the money go to? Historically, this newly-created easy money went directly to the big banks, a sort of UBI for the rich. So of course the effects will be at least somewhat destabilizing, as it is so lopsided. We all know now that the "trickle-down" theory is BS, so why don't we simply give all newly-created money to We the People instead? That would have to be better IMHO.