An Economic Explanation for the Youth Mental Health Crisis

Preface

Here is the X thread that summarizes this post.

Here is a podcast of this post made using Google’s NotebookLM:

Introduction

When I was growing up, a close relative attempted suicide twice during her teenage years. The first time, she called it an accident, but after the second overdose, it became clear these were not accidents. Thankfully, she received the help she needed, and today she is alive and well. Her experience is reflective of what so many teens face today—easy answers often prevent us from understanding what’s really happening beneath the surface.

When it comes to the youth mental health crisis, many people see smartphones and social media as the primary cause, which has led some to advocate for prohibiting their use by teens altogether. This perspective, called Smartphone and Social Media Theory (SSMT), offers a seemingly straightforward and actionable solution. However, I believe that this approach oversimplifies a complex issue. By focusing on smartphones and social media, we are overlooking the deeper causes of distress that young people are facing today.

To illustrate how our fixation on technology can prevent us from truly understanding and supporting young people, consider the following NPR segment, in which Anya Kamenetz interviewed 14-year-old Abby and her parents, Ellie and Geoff.

Overall, Abby is doing well—she has friends and gets good grades. However, her parents are concerned because she is always on her phone, which makes them feel disconnected from her. Below is an abridged version of the interview:

Kamenetz: What do you wish that grown-ups knew about the phone?

Abby: Taking it away won’t eliminate problems because it’s not the sole reason that they existed in the first place.

Ellie: Can I say something? I recently showed Abby an article about children, teenagers with depression and the screens and that there’s a rise in depression and a rise in suicide along with a rise in screen use.

Kamenetz: And so what did you think when your parents showed you that article?

Abby: It said it like it’s the only reason and not, like, stress from school, from, like, other people, from other things happening. It’s just - it always acts like the iPhones are the only reason that kids are depressed and can’t sleep and have all of these problems. It’s never the only reason.

This exchange demonstrates misattunement—a disconnect in emotional understanding. In this case, Ellie had the perfect opportunity to attune to her daughter—to connect with her emotionally by engaging with empathy and curiosity, and seeking her collaboration to address her concerns. Instead, Ellie focused on blaming smartphones, missing the chance to truly understand and support Abby.

Since SSMT presents as a clear solution, this makes it easy for alternative explanations to be overlooked—as seen in Abby’s case. This kind of oversight isn’t limited to advocates of SSMT—I’ve seen it firsthand in my own family. My relative’s parents also believed they knew what was best, and this belief often overshadowed the opportunity to understand her perspective. During disagreements, I often heard her plead with them to “just listen.”

Similar interactions to Abby’s are happening every day between teens and their parents. SSMT advocates, including Jonathan Haidt, share a message that strongly resonates with parents’ concerns: “If you want to keep your kids safe, then don’t give them a smartphone.” Ellie, understandably, wants to protect her daughter. While parents do their best, it’s easy to miss chances to fully understand their children’s experiences, especially when the issue is complex and emotions are high. Teens like Abby frequently feel unheard because easy answers lead parents to talk at their teens rather than engage in meaningful conversations with them. This creates a disconnect, leaving teens feeling isolated and misunderstood.

Abby experienced a disconnect with her parents due to their focus on her phone use, but an even stricter approach could potentially deepen that very disconnect. A rigid, one-size-fits-all solution like prohibiting smartphone and social media use until a certain age might appeal to parents looking for a clear-cut approach, but this ultimately overlooks their children’s individuality. Although Haidt acknowledges this potential downside, he still recommends it for the sake of convenience:

I’ve concluded that rather than the common sense approach of “oh, every kid is different; your kid may have a different path with their own pluses and minuses,” which just leads to constant conflict, confusion, and such a mess, we should establish a very clear boundary that everyone can stick to: no smartphone before high school. It’s not even up for negotiation…Also, no social media until age 16. These are norms that we can stick to…parenting has always required parents to set boundaries, and kids learn to live within those boundaries—they learn to control their wants and control themselves.

In our time of crisis, the concerns expressed by Haidt and others are understandable, and there are valid criticisms of social media companies. However, prohibiting smartphone and social media use addresses only a symptom, missing deeper causes of teen distress.

Rather than rigid, top-down control, a more effective approach to understanding teen behavior involves considering their core psychological needs. Self-Determination Theory (SDT) provides a useful lens to understand why many teens are so absorbed by their devices. SDT, developed by Richard Ryan and Edward Deci, identifies three essential psychological needs for well-being: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Autonomy means having control over one’s actions, competence is feeling capable, and relatedness involves feeling connected to others. For his book Indistractable (2019), Nir Eyal consulted Richard Ryan to better understand why many young people often find themselves caught in a digital trance:

When considering the state of modern childhood, Ryan believes many kids aren’t getting enough of the three essential psychological nutrients—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—in their offline lives. Not surprisingly, our kids go looking for substitutes online. “We call this the ‘need density hypothesis,’” says Ryan. “The more you’re not getting needs satisfied in life, reciprocally, the more you’re going to get them satisfied in virtual realities.”

Ryan’s research leads him to believe that “overuse [of technology] is a symptom, one indicative of some emptiness in other areas of life, like school and home.” When these three needs are met, people are more motivated, perform better, persist longer, and exhibit greater creativity.

While parents address their children’s unmet needs, they can also help their children find a healthy balance with screen time:

Ryan isn’t against setting limits on tech use but thinks such limits should be set with the child, and not arbitrarily enforced because you think you know best. “Part of what you want your kid to get from that is not just less screen time, but an understanding of why,” he says. The more you talk with your kids about the costs of too much tech use and the more you make decisions with them, as opposed to for them, the more willing they will be to listen to your guidance.

We can’t solve all our kids’ troubles—nor should we attempt to—but we can try to better understand their struggles through the lens of their psychological needs. Knowing what’s really driving their overuse of technology is the first step to helping kids build resilience instead of escaping discomfort through distraction. Once our kids feel understood, they can begin planning how best to spend their time.

Eyal’s approach stands in stark contrast to Haidt’s more dismissive stance:

we should expect to have heated discussions about the role technology plays in our homes and in our kids’ lives, just as many families have fiery debates over giving the car keys to their teens on a Saturday night. Discussions and, at times, respectful disagreements are a sign of a healthy family…when we discuss our problems openly and in an environment where we feel safe and supported, we can resolve them together.

Eyal points out that when parents don’t have their child’s agreement, they are “forcing them to do something they didn’t want to do [which amounts] to coercion and would only breed resentment.”

To be clear, I am not blaming parents. They are doing their best with the knowledge they have. I believe that once they understand what is happening, they will be able to adapt—just like my relative’s parents did. My goal is to put what’s going on into context so parents can better understand both their children and their own behavior, ultimately improving their relationship before it’s too late. I see SSMT as a barrier to this. However, once we truly understand what’s happening, we will see that SSMT is just a symptom of a larger problem.

The crisis we are facing is a societal issue that impacts interactions between individuals, such as the parent-child relationship. Therefore, we need to take action both at the family level and on a broader societal scale to address this crisis.

Here’s my plan: In this post, I will introduce an alternative explanation for the youth mental health crisis. In future posts, I will explore why American teens are suffering more than their peers in other countries, outline an alternative form of parenting that respects young people, and propose a solution to this societal issue.

Drawing on economic trends, my theory—Easy Money Distress Theory—aims to explain why autonomy, competence, and relatedness have been on the decline, contributing to the mental health crisis among today’s teens.

Let’s start by looking at the data.

Suicide and Homicide

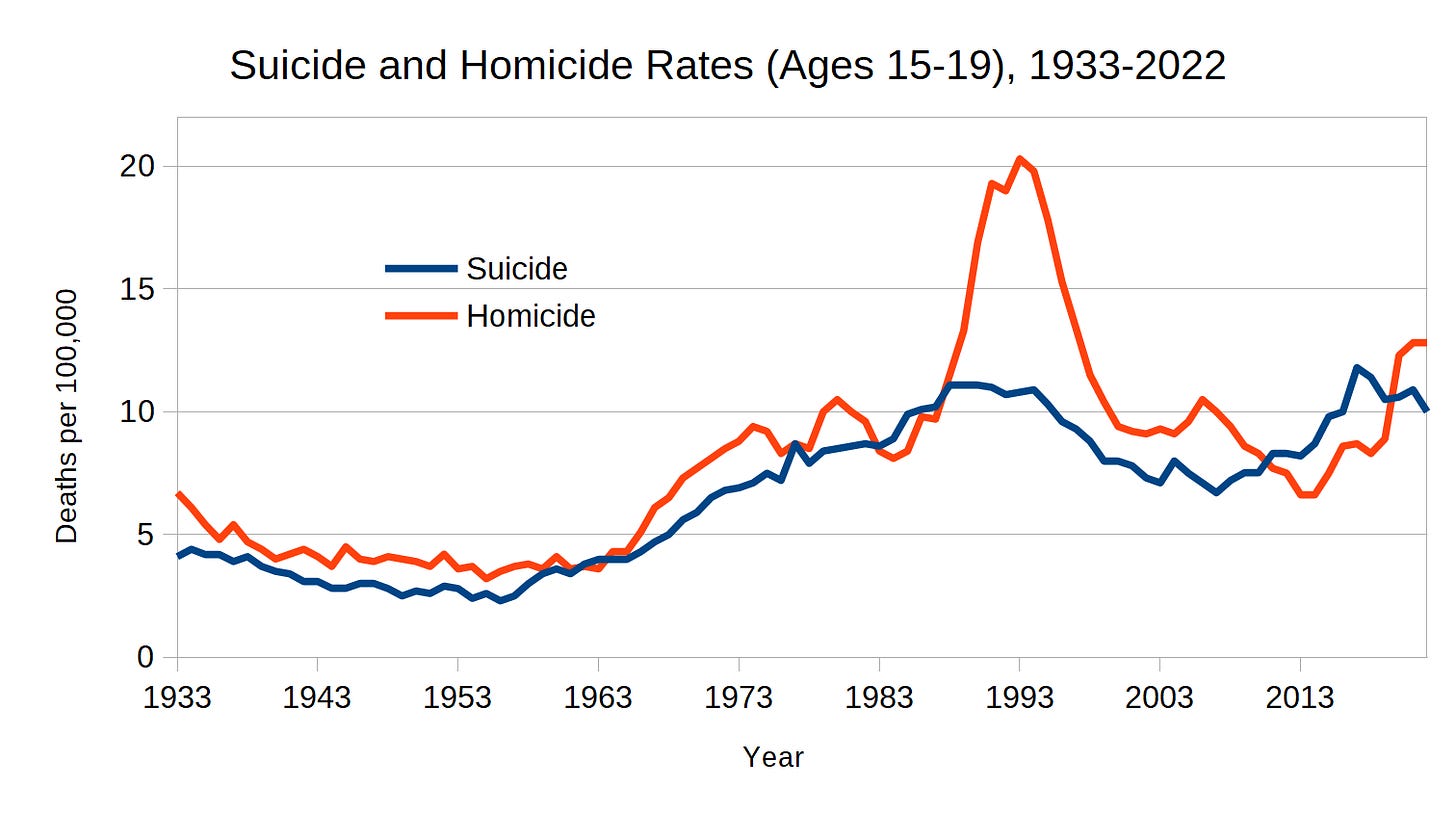

My theory can help explain both the suicide and homicide rates among young people. To examine these rates as far back as possible, I referred to Holinger et al. In their book Suicide and Homicide Among Adolescents (1994), they explain that “beginning in 1933, the data include the total U.S. population, not samples; prior to 1933, not all states were included in the national mortality data.” Using the data from Holinger’s book and the CDC, I developed Figure 1 to depict suicide and homicide rates from 1933 to 2022 for individuals aged 15 to 19.

As shown in the graph above, there is a clear correlation between teen suicide and homicide rates. This correlation suggests they may share a common root cause.

The Failure of Smartphone and Social Media Theory

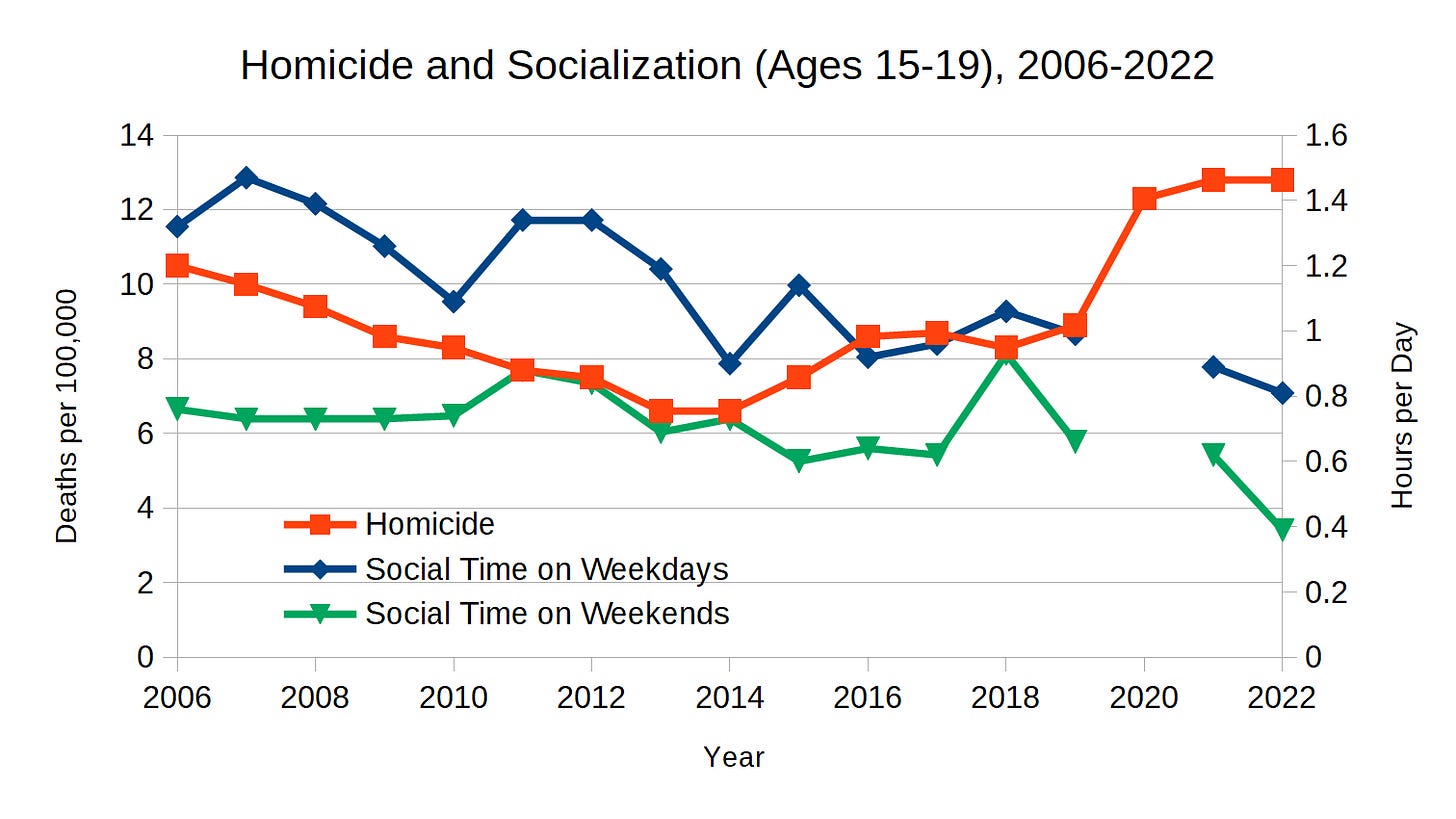

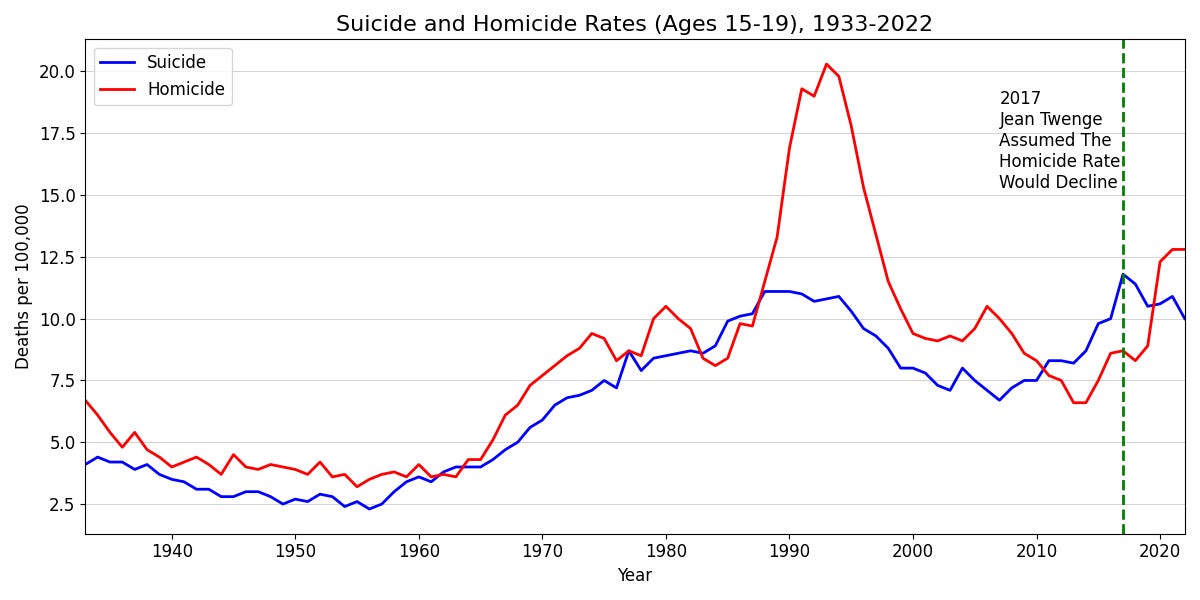

SSMT proponent Jean Twenge suggested that she could predict trends in teen suicide and homicide rates using her causal explanation for SSMT. In her 2017 book iGen, she argued that declining socialization—caused by increased smartphone use—was driving both the decrease in teen homicide and the rise in suicide:

Since 2007, the homicide rate among teens has declined, but the suicide rate has increased. The steady decline in teen homicide from 2007 to 2014 looks very similar to the decline in in-person social interaction…As teens have spent less time with one another in person, they have also become less likely to kill each other…The astonishing, though tentative, possibility is that the rise of the smartphone has caused both the decline in homicide and the increase in suicide. With teens spending more hours with their phones and less with their friends, more are becoming depressed and committing suicide and fewer are committing homicide.

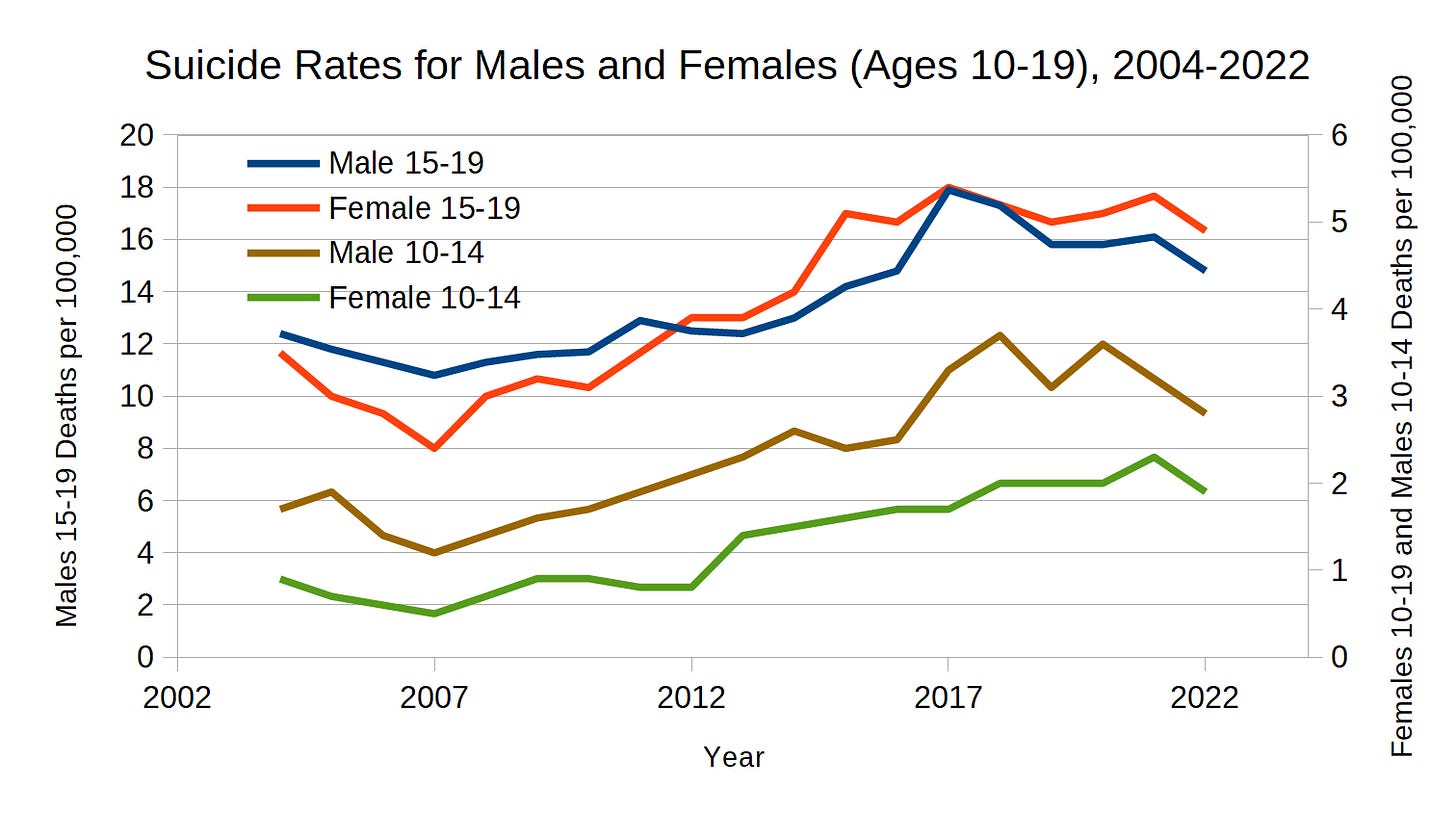

Contrary to Twenge’s assumption about the relationship between in-person interaction and homicide, Figure 2 shows socialization continues to decline while homicide has been increasing since 2014.

As we saw earlier, suicide and homicide are correlated for teens:

The fundamental flaw of SSMT is its failure to account for the correlation between teen suicide and homicide rates.

Youth suicide and homicide are two sides of the same coin.

We’ll come back to SSMT in a moment. For now, I’d like to share a metaphor that will help us later on.

The Burden Bag Metaphor

Imagine society as a group of travelers, where adults must carry a burden bag filled with rocks. As time passes, the burden supply grows, and the burden supply growth—the rate at which the burden increases—can vary significantly. When the burden supply growth accelerates too quickly, many travelers struggle to stay balanced, while others are crushed under the sudden weight.

Parents, feeling overwhelmed by their own burdens, pressure their children to prepare for the future by undergoing a training program to build physical strength, ensuring that they will be capable of carrying their own burden one day. This pressure often leads children to prioritize meeting parental expectations at the cost of their own well-being, feeling as though they must always prove they are ready for the weight of future burdens.

To cope with the rigorous training program and the expectations from parents, young people turn to whistling. Whistling serves two purposes: it distracts them from the pressures and allows them to communicate with one another—sometimes in ways that avoid the prying ears of parents.

In this metaphor, whistling represents social media, which young people use both to escape and connect. The dual purpose of whistling—as personal comfort and secret communication—mirrors the role social media plays in teens’ lives today, offering temporary relief, a sense of connection, and a way to carve out private spaces.

I’ll explain what the burden supply, the burden supply growth, and the training program represent as we continue our discussion.

Suicide, Homicide and the Economy

Let’s explore what’s behind the correlation between homicide and suicide.

Paul H. Holinger, in his book Violent Deaths in the United States (1987), explains the relationship between suicide, homicide and the economy as observed by Meyer Harvey Brenner:

Brenner’s (1971, 1979) work on the relationship between economic cycles and mortality…demonstrated that indicators of economic instability and insecurity, such as unemployment, were associated over time with higher mortality rates. The explanation for this association was that the lack of economic security is stressful—social and family structures break down, and habits that are harmful to health are adopted. The effect may manifest acutely as a psychopathological event (e.g., suicide and homicide) or, after a time lag of a few years, as a chronic disease (e.g., cancer or heart disease). Brenner’s conclusions…showed that indices of acute pathological disturbances, including suicide and homicide, rose within a year of increased unemployment rates.

SSMT advocate Jean Twenge claims she has proven that economics has nothing to do with the youth mental health crisis by citing low unemployment numbers. However, unemployment is not the only factor contributing to the negative health effects on the population during economic downturns. A study by Vandoros and Kawachi (2021) examined the relationship between economic uncertainty—measured by the Economic Policy Uncertainty Index—and the suicide rate from 2000 to 2017. The study found that “Economic uncertainty is positively associated with suicide when controlling for unemployment.” The authors provided a possible explanation for why unemployment alone does not account for the link between economic conditions and suicide rates:

People who are not unemployed might still face increased levels of economic uncertainty. For example, during the 2008 Great Recession, people may not have lost their jobs, but they might have been greatly affected by the crash in housing prices, resulting in them “going underwater”, i.e., owing more on their mortgages than the value of their houses. A big increase in indebtedness is likely to have led to financial worries, and may have affected planning for retirement, etc.

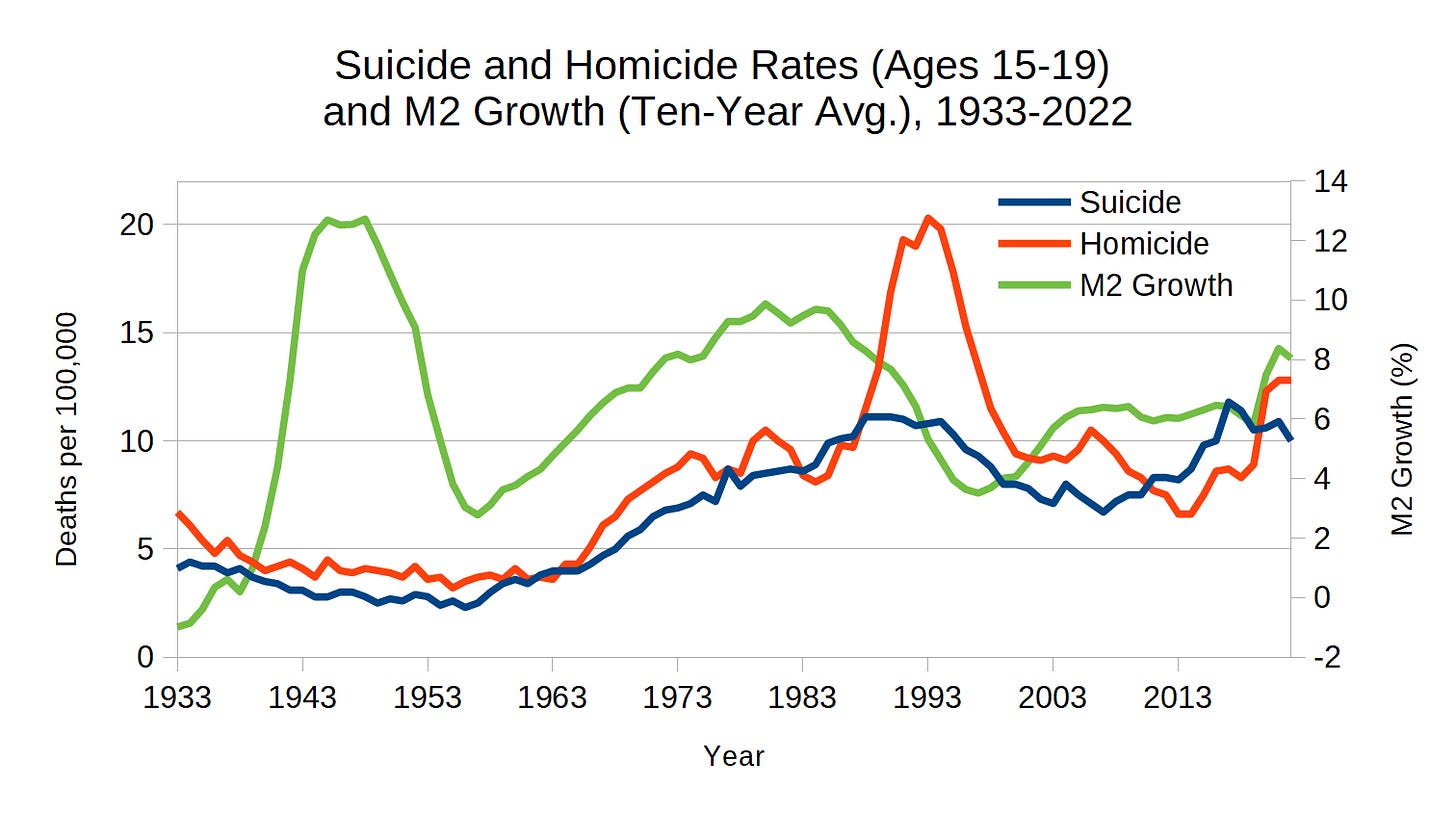

According to Austrian Business Cycle Theory (ABCT), the economic boom and bust cycle is driven by increases in the money supply. For our discussion, we will use the M2 money supply, as it is the broadest measure of money supply tracked by the Federal Reserve. We will also discuss M2 growth, which refers to the percentage change in the M2 money supply.

In the metaphor, I described adults carrying burden bags filled with rocks that grew heavier over time. These burden bags symbolize the weight of economic pressures on individuals, while the burden supply represents the M2 money supply. Similarly, the burden supply growth represents M2 growth. Just as a sudden increase in the burden supply growth can destabilize travelers, rapid increases in M2 growth create instability for families, leading to distress.

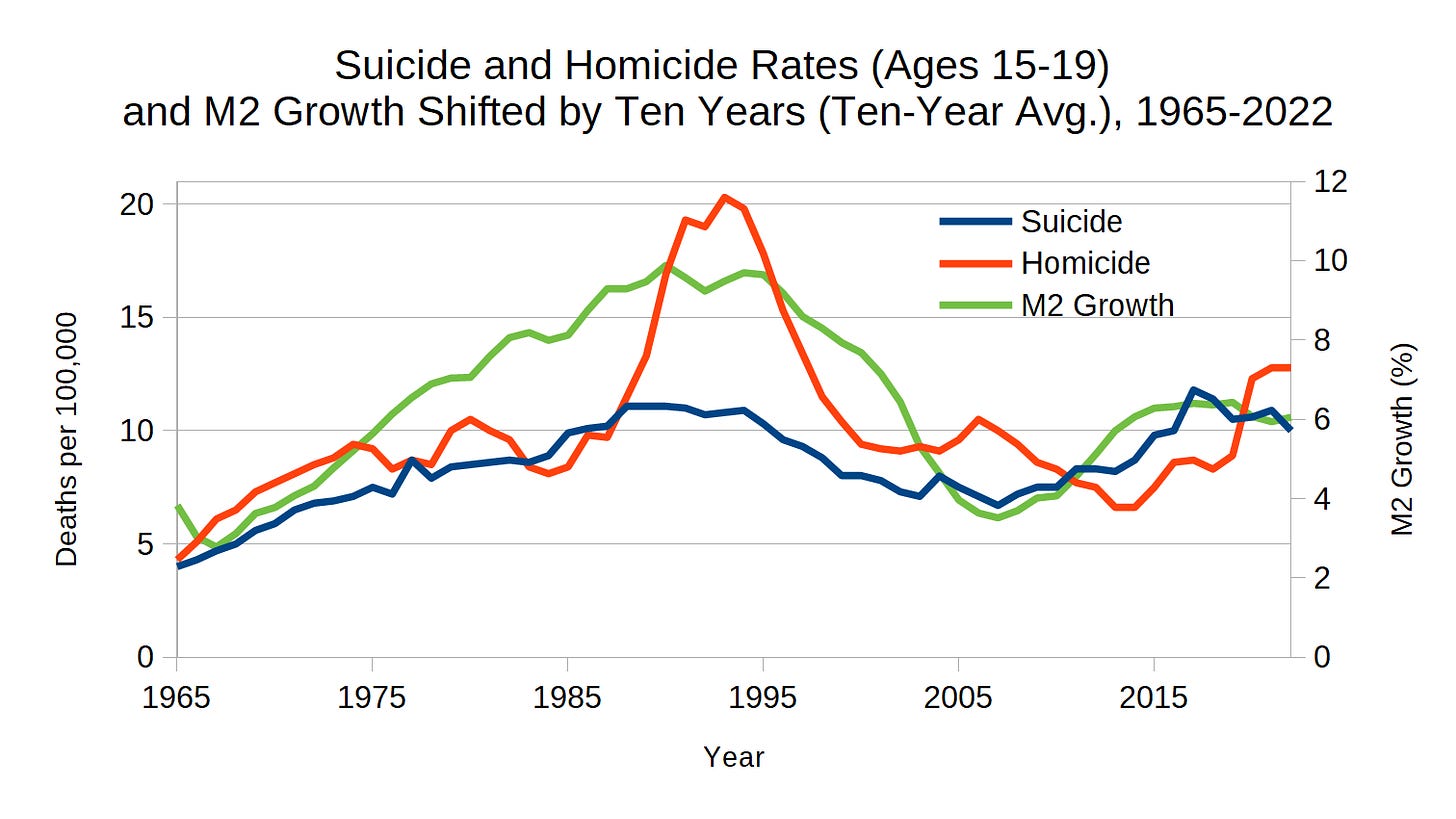

When we synthesize Brenner’s observations with the ABCT, we can see the relationship between suicide, homicide, and M2 growth. Figure 4 presents the homicide and suicide rates for individuals aged 15 to 19 alongside the ten-year moving average of M2 growth.

Given the delay between M2 growth and the suicide and homicide rates, Figure 5 presents the same data, but with M2 growth time-shifted by ten years to show the correlation between all three variables. This correlation suggests that young people are particularly vulnerable to the economic instability and insecurity that follow significant increases in the money supply.

Two of the three M2 money supply waves between 1933 and 2022 align with the two waves of suicide and homicide rates. The first M2 money supply wave did not impact suicide or homicide rates because it coincided with World War II. Many reasons have been suggested for why these rates remained low during the war, but two primary factors stand out. The first was low unemployment, which alleviated a significant aspect of financial stress for many. The second was a unifying sense of purpose—defeating the enemy. This collective mission gave Americans a reason to accept many of the negative consequences of the war at home, such as price inflation and internment camps. During this time, individuals focused on survival and service over personal struggles.

In his book The Great Wave (1996), David Hackett Fischer describes how Americans responded to the countermeasures enacted to combat the effects of price inflation during World War II:

In the United States, a regulatory system that included rationing and price controls worked remarkably well to stabilize the booming economy. A black market developed for scarce goods, but most Americans willingly accepted a more highly regulated economy as part of the war effort...The contribution of economic regulation in World War II was both material and moral. It fostered a sense of fairness and justice, and sustained collective effort in a nation that was united as never before.

More Money, More Problems

Increases in the money supply can contribute to economic precarity — a condition marked by financial instability and insecurity — through two main mechanisms: price inflation and malinvestment. Price inflation occurs when an increased money supply leads to more money chasing fewer goods, causing a rise in the cost of living. Malinvestment arises when low interest rates encourage risky investments, creating unsustainable asset bubbles that, when they collapse, result in economic disruption and job losses. All of these factors contribute to a sense of unpredictability, making it harder for individuals and families to maintain their financial security.

Let’s take a look at the two most significant recent economic events: Stagflation and the Great Recession. Both share a common root cause: the Federal Reserve’s loose monetary policy. An analysis by Robert B. Barsky and Lutz Kilian (2001) shows that the primary factor behind the stagflation of the 1970s was the Federal Reserve increasing the money supply. Similarly, as Thomas E. Woods Jr. notes in his book Meltdown (2009), the main factor leading to the Great Recession was also the Federal Reserve increasing the money supply. For simplicity, I will focus only on the more recent event.

The distress following the Great Recession has contributed to a rising youth suicide rate, which continues to climb due to persistent financial hardships. Figure 6 shows that the teen suicide rate has been increasing since 2007.

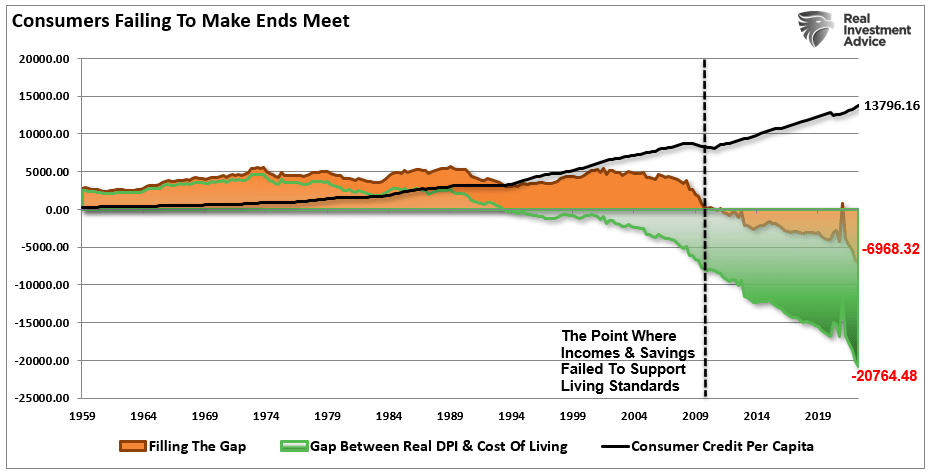

Lance Roberts demonstrates that, after 2009, income and savings have failed to support living standards:

Between 1959 and 1990, individuals could sustain their inflation-adjusted standard of living with only incomes and savings. There was roughly a $4,700 surplus yearly as households had very low debt levels. However, beginning in 1990 and accelerating following the Financial Crisis in 2008, households required an increasing level of debt to “fill the gap” between what income and savings could afford and the cost of the current living standard. You will notice a brief spike in 2020-2021 as “stimmy checks” hit household bank accounts [Figure 7]. However, that surplus has reversed to the deepest deficit on record.

My Theory on the Youth Suicide and Homicide Rate

A significant increase in the money supply often leads to economic instability and insecurity, creating widespread distress. For some, this distress affects their mental health so severely that they die by suicide. In other cases, the distress turns into frustration and anger, sometimes culminating in violence.

I call my theory Easy Money Distress Theory (EMDT). Easy money refers to the Federal Reserve’s practice of increasing the money supply, typically by lowering interest rates to make borrowing cheaper and stimulate economic growth. Throughout my writing, I use easy money interchangeably with increases in the money supply, as they essentially represent the same concept.

Before continuing, I want to make it clear that my theory addresses the primary factor, though not the only factor, behind the changes in the rates of youth suicide and homicide in the United States. While I acknowledge that my theory may have limitations, I believe it offers valuable insights that can spark further discussion and research into the role of economic conditions in shaping societal trends. If it does, I would consider that a success.

History

SSMT focuses heavily on teen girls’ social media use, which reflects real concerns. To understand the appeal of SSMT more deeply, it helps to consider it within a broader context of societal concerns about young women’s behaviors over time. History is filled with examples of adults expressing concern over new teen activities, often blaming them for broader social problems. The patterns in these instances provide valuable lessons for how we can interpret today’s fears. Below are moral panics centered around teen girls, as described in Shayla Thiel-Stern’s 2014 book, From the Dance Hall to Facebook: Teen Girls, Mass Media, and Moral Panics in the United States, 1905-2010:

1. Dance Hall Moral Panic (1905-1928)

2. Girl Athlete Moral Panic (1920-1940)

3. Rock and Roll Moral Panic (1956-1959)

4. Punk Rock Moral Panic (1976-1986)

5. Internet Social Networking Moral Panic (2004-2010)

Thiel-Stern provides a brief summary of the moral panics:

1. the popularity of dance halls with working-class teen girls in the early 1900s and social reformers’ efforts to reform and outlaw dance halls;

2. the perceived problems associated with teen girls participating in “sports of strife,” or strenuous athletics—specifically, track and field (including a fear of hurting girls’ ability to reproduce in the future and the issue of participants appearing too “masculine” while running);

3. teen girls’ public demonstration of emotion and sexuality in their adulation of Elvis Presley in the mid-1950s and the perceived link between juvenile delinquency (specifically, promiscuity) and enjoying his music;

4. the concern in the late 1970s and early 1980s that teen girls who embraced punk rock music and fashion were not feminine enough and that their physical rebellion (which in the media was tied almost entirely to their appearance in public) could be linked to their own moral decay, cultural deviance, or inability to one day conform to dominant cultural notions of femininity; and

5. teen girls’ widespread use of social networking sites such as Facebook and MySpace since 2004, with special attention paid to issues of sexual predation, sexting, and cyberbullying and to the general fear that girls either show excessive sexual agency or are victimized online.

The following quotes from Thiel-Stern highlight her findings about these moral panics.

The truth is, girls just want to have fun:

they are not committing crimes but rather enjoying their leisure and experiencing recreation by dancing, running, listening to music, attending live events, and using the Internet to communicate with the world.

The moral panics were never really about the welfare of teen girls; they were about our own anxieties:

Media-fueled crises and moral panics arguably have been created to maintain the power of the status quo and in turn affect the social construction of reality for all media audience members...Often, gender seems to relate directly to widespread public social anxieties within the larger U.S. population, and published and broadcast news often feed these anxieties.

The media profits off our fears because we continue to believe in the vulnerable teen girl narrative:

Reporting that fosters gendered crises and moral panics about teen girls in public recreational space is popular among U.S. audiences; otherwise, news organizations would not bother.

Society is conditioned to see her as a victim who must be policed and saved, and this is the dominant narrative told by a variety of American media from the early twentieth century to contemporary society.

In the end, more restrictions are placed on girls:

The remedy for such panic is usually an enactment of social control over the wayward girls—sometimes through law and policy and sometimes through cultural punishment that tends to further limit how girls interact in public space.

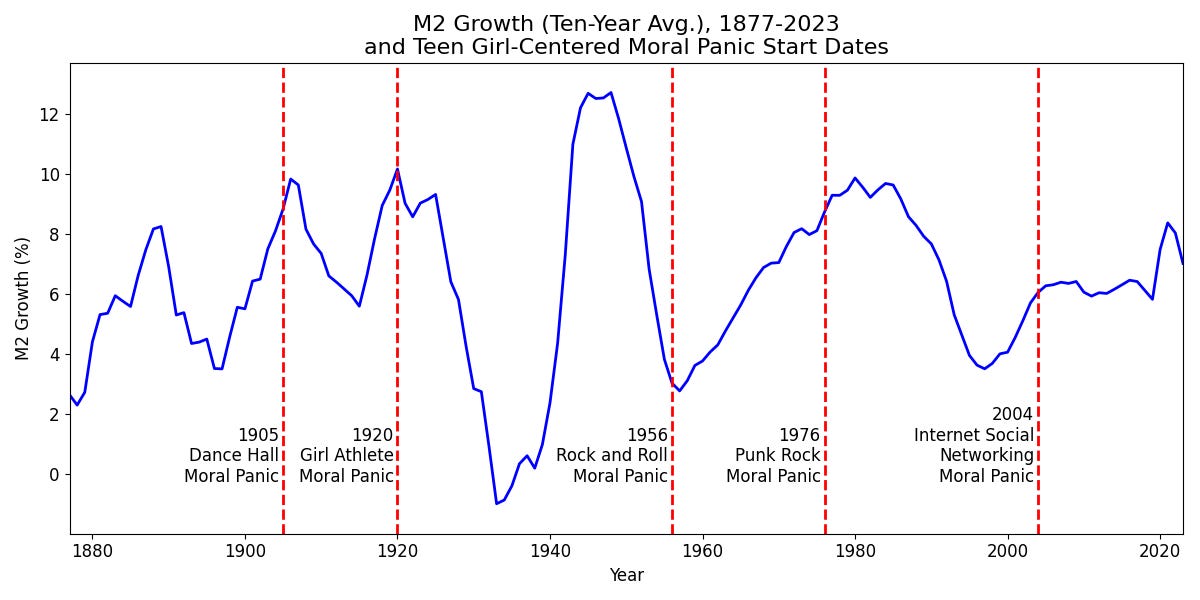

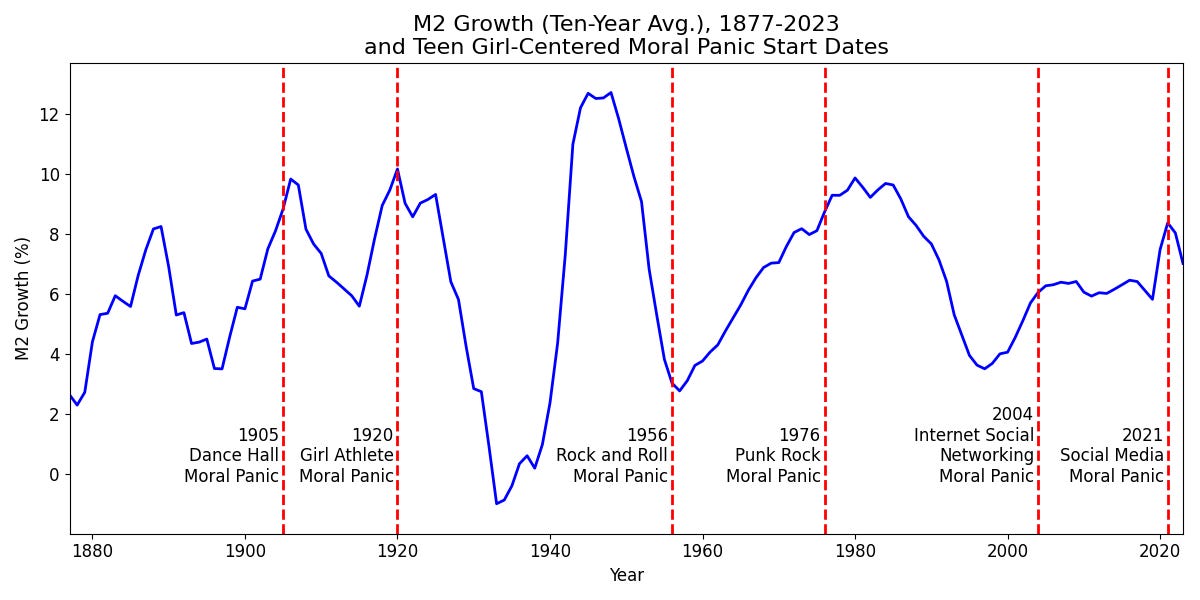

As Thiel-Stern points out, moral panics were really about our own anxieties. To explore whether economic factors contribute to these anxieties, we can use the economic measure of M2 growth. Comparing M2 growth with the timing of these moral panics suggests that economic conditions—particularly instability and insecurity—may be a significant driver of these anxieties. Figure 8 shows the ten-year average of M2 growth, with vertical lines marking the onset of moral panics involving teen girls. This historical pattern is telling: moral panics often follow periods of significant increases in the money supply, suggesting that economic conditions play a significant role in fueling societal fears.

Let’s take a moment to understand what is happening here. Teen girls are enjoying themselves independently from the adults in their lives. At the same time, adults are experiencing distress due to economic instability and insecurity brought about by increases in the money supply. The media profits from this widespread anxiety by offering a seemingly clear and actionable solution: save the delicate, wayward teen girl from the potential harms of her activities. Scapegoating and restricting the behavior of girls unites us and gives us a sense of clear purpose during economic upheaval. On the surface, this feels empowering, but in reality, it weakens us. By allowing easy money policies to continue, we are ensuring mounting economic instability and insecurity.

The negative psychological effects of policies that increase the money supply are what I refer to as easy money-induced distress. A mass movement seeking to restrict the behavior of a peaceful group during heightened periods of this distress is what I call an easy money-induced moral panic.

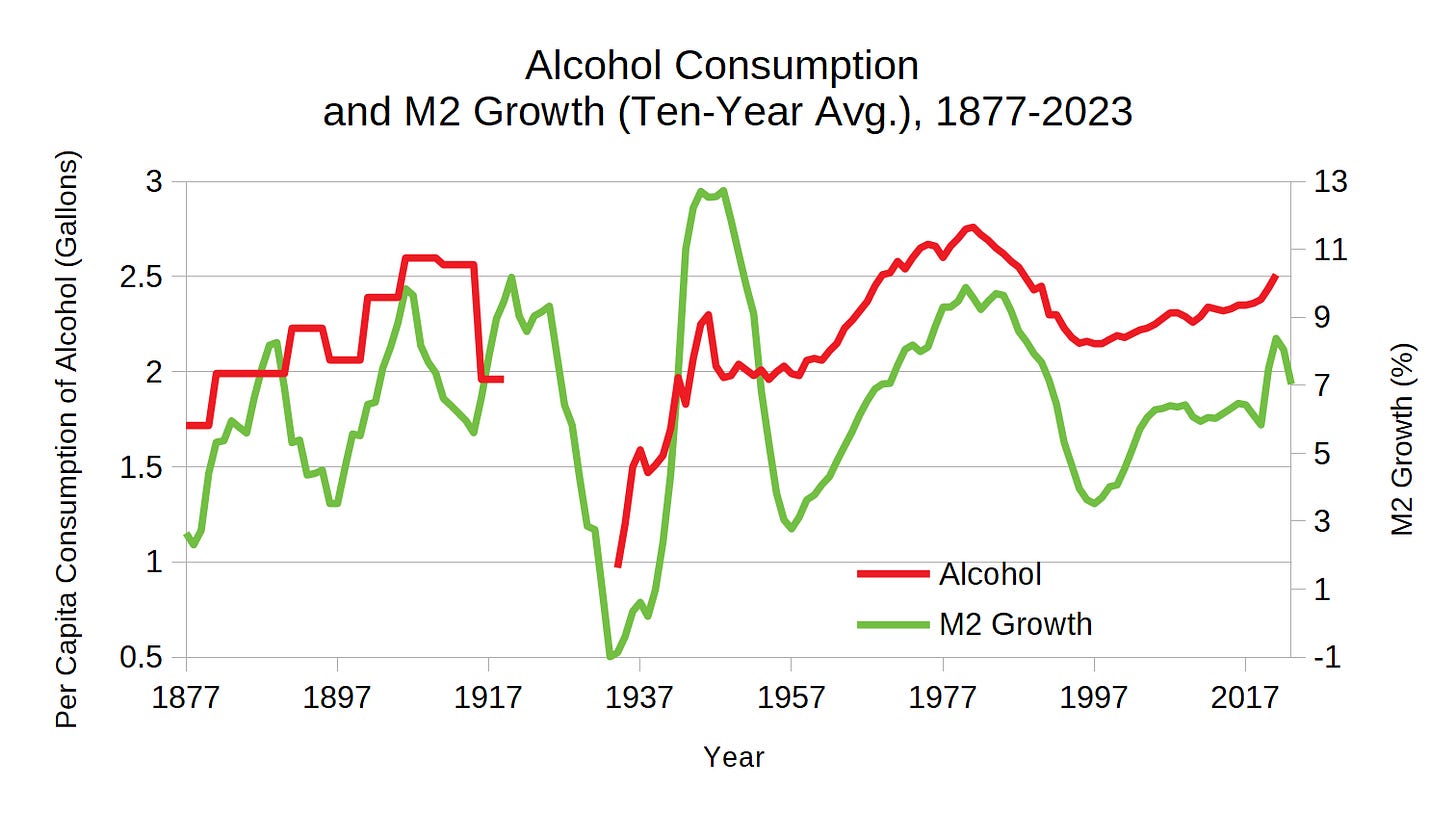

Just as easy money-induced distress has led to scapegoating teen behaviors, similar patterns have targeted adults, such as those that led to alcohol prohibition. The novelist John Steinbeck wrote, “alcohol has been an anodyne, a warmer of the soul, a strengthener of muscle and spirit.” An anodyne is something that soothes distress, another word for a coping mechanism. The increased use of anodynes like alcohol often coincides with heightened distress. As Figure 9 shows, alcohol consumption has generally followed the trend of M2 growth. I believe alcohol prohibition was an example of an easy money-induced moral panic, as alcohol was blamed for many of the troubles of the early 20th century—troubles that were likely the side effects of easy money policies.

Another Moral Panic

Based on history, the current level of concern over smartphones and social media was almost inevitable. Thiel-Stern accurately predicted that the Internet would remain a source of fear for adults:

Stories about scandal and deviance will likely continue to abound with regard to the Internet because it continues to be a novel technology with new applications being developed every day; young people often will be the first to discover them—a fact that makes most adults all the more nervous.

The movement to prohibit smartphone and social media use among teenagers resembles a moral panic, largely because it lacks a clear causal explanation. As we’ve discussed, any valid explanation for SSMT must also account for the correlation between teen suicide and homicide.

The data for SSMT comes primarily from three sources: self-report surveys, correlational studies, and experiments. The first two cannot prove causation; as for the third, Peter Gray explains why social media experiments have not proved causality:

The first problem is the placebo effect…With drug studies you can hide from the subjects which ones are getting the drug and which are getting the placebo, but with technology studies the subjects naturally know which group they are in. There is no way to show that an effect of reducing social media is not just a placebo effect.

The second problem is what researchers call the demand effect. Subjects in research experiments are very good at guessing what the research hypothesis is and, consciously or unconsciously, are motivated to prove the hypothesis correct.

Gray also raises the issue of self-selection bias:

We can assume that subjects in social media experiments are aware of the common belief that social media use has harmful psychological effects, and it even seems likely that such awareness is what led them to volunteer to be in the experiment.

The concern over social media’s impact gained so much traction in 2021 that social media executives were called to testify before the U.S. Senate. As expected, the hearing reflected the characteristics of a typical moral panic. As Mike Masnick noted, the second hearing, like the first, “turned into another ridiculous Senate hearing in which old men yell at social media execs about how they’re harming kids.”

Figure 10 shows the ten-year moving average of M2 growth alongside all the moral panics centered around teen girls since 1905, including the current one. Like previous panics, this one emerged after a significant increase in the money supply, making it an easy money-induced moral panic.

Risk Versus Harm

There are legitimate concerns about social media, just as there were during previous moral panics. However, the problem with these panics is that they often conflate risk with inevitable harm, leading to over-reactive measures like prohibiting the activity altogether. This approach leaves young people with nothing to learn except that might makes right. It can even be counterproductive if teenagers continue to engage in the prohibited activity secretly, which may put them at an even greater risk of harm.

As danah boyd and Mike Masnick argue, reducing risk is not about eliminating it entirely—it’s about preparing individuals to face challenges effectively. For instance, learning to cross a street involves risk, but when parents teach their children how to cross safely, the potential for harm becomes unlikely. Likewise, deciding when a child is ready to cross alone shouldn’t be based on an arbitrary age but rather on their readiness and the parent’s judgment.

boyd was the first to recognize how calls for technology prohibitions often stem from conflating risk with inevitable harm—a mistake we might term the prohibitionist fallacy. Rather than prohibiting smartphones and social media, a more reasonable approach is to help young people become competent at managing online risks.

In her book The Art of Screen Time (2018), Anya Kamenetz illustrates how simple, honest conversations between parents and children can have a lasting impact on children’s behavior and self-esteem:

One of [Eric] Rasmussen’s studies asked whether parents had discussed pornography with their middle-school and high-school–aged children—not necessarily with blanket condemnation, but honestly sharing their values. When kids whose parents had discussed porn honestly with them got to college, they were less likely to view porn themselves. And if they were in a relationship with someone who looked at porn, it was less likely to affect their self-image or self-esteem. “When you’re dating someone who looks at porn your self-esteem takes a hit,” Rasmussen says, citing other research. “Except if your parents talked to you about it.” Whether it’s because the parents who manage to broach this uncomfortable topic generally have closer, stronger relationships with their kids, or healthier attitudes about sex, or for some other reason, the porn talk seems to have a lasting protective effect, like an inoculation.

A young person’s social media use doesn’t have to follow an all-or-nothing approach—it can be gradual. Learning to use social media can be seen as similar to learning how to ride a bicycle, which often begins with training wheels and parental guidance. As young people become more competent, parents can gradually grant more independence. Just as a young person gains the skills to explore the physical world independently on their bike, they can also be ready to explore the digital world—guided by the same gradual approach. Young people can enjoy the benefits of any technology—whether it’s a bike or a smartphone—while mitigating potential downsides.

Interestingly, in the 1890s, there was a moral panic over young women riding bicycles. In her book Wheels of Change (2011), Sue Macy describes the restrictions placed on teenage girls before bicycles became popular, offering insight into the context behind this panic:

With the rise of industry and the move from a rural to an urban economy in the 19th century, American women had become increasingly confined to their homes.

Young girls could play outside, but when they matured, their freedom of movement was greatly restricted. “At sixteen years of age, I was enwrapped in the long skirts that impeded every footstep,” remembered Frances Willard, who in 1895 wrote a best-selling account of how she learned to ride a bicycle at age 53.

Macy reveals that the concerns surrounding young women cyclists were about more than just physical well-being:

Although they rarely said it, some of those who focused on the effects of cycling on women’s sexual and reproductive health had a greater concern. They worried that the bicycle might permanently change women’s role in society by fostering their independence. At the time, the social lives of many young women were strictly supervised, but cycling allowed these women to escape their parents’ watchful eyes. “Parents who will not allow their daughters to accompany young men to the theatre without chaperonage allow them to go bicycle-riding alone with young men,” newspaperman Joseph Bishop wrote in an assessment of the impact of the bicycle in 1896. This was one of the matters that motivated Charlotte Smith to declare that the bicycle had brought about “the alarming increase of immorality among young women in the United States” because of the “evil associations and opportunities” it made possible.

Peter Gray’s Three Questions

Now that I have provided a general overview of my theory and examined the history, we can begin to explore what is contributing to our current crisis.

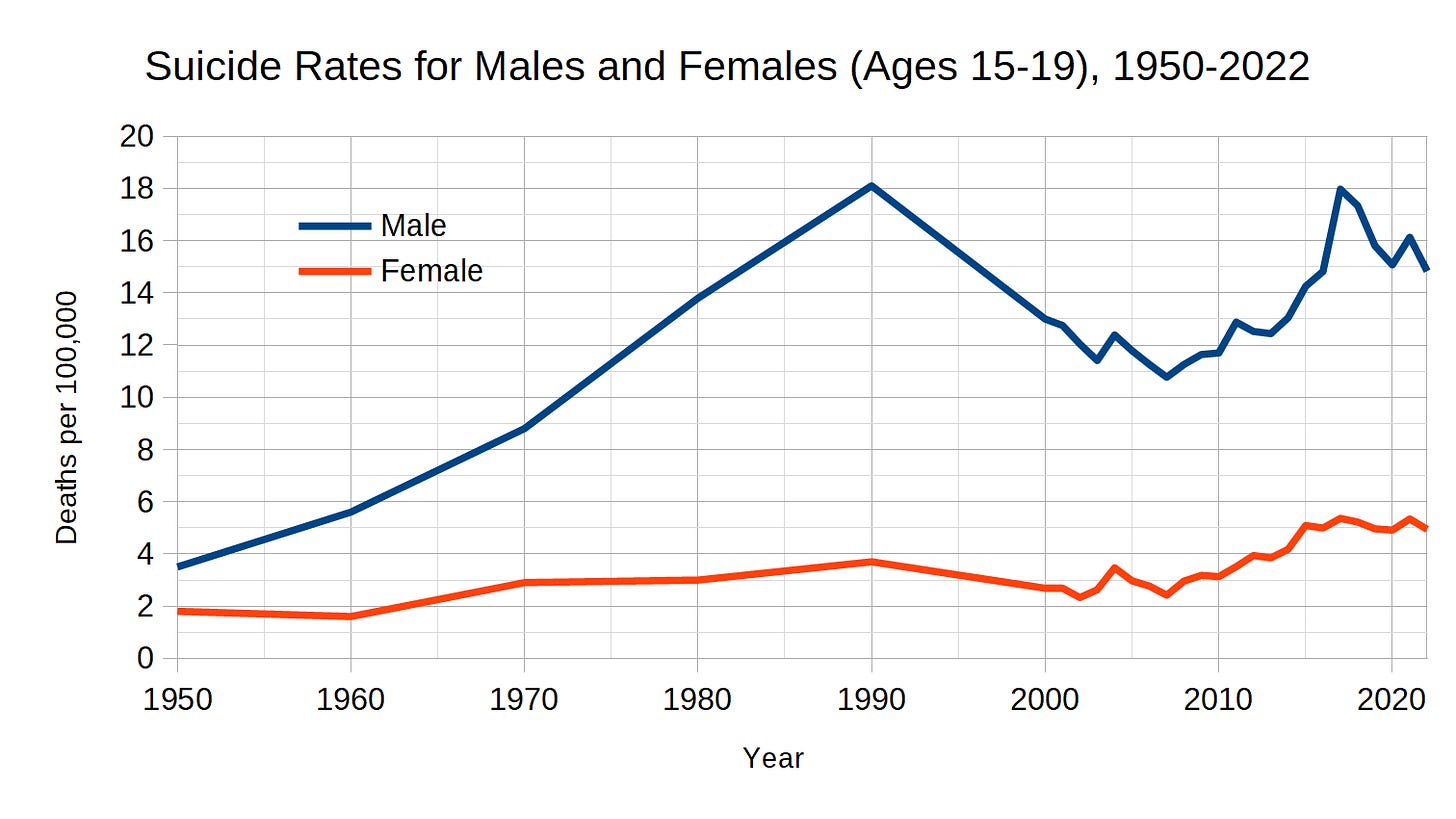

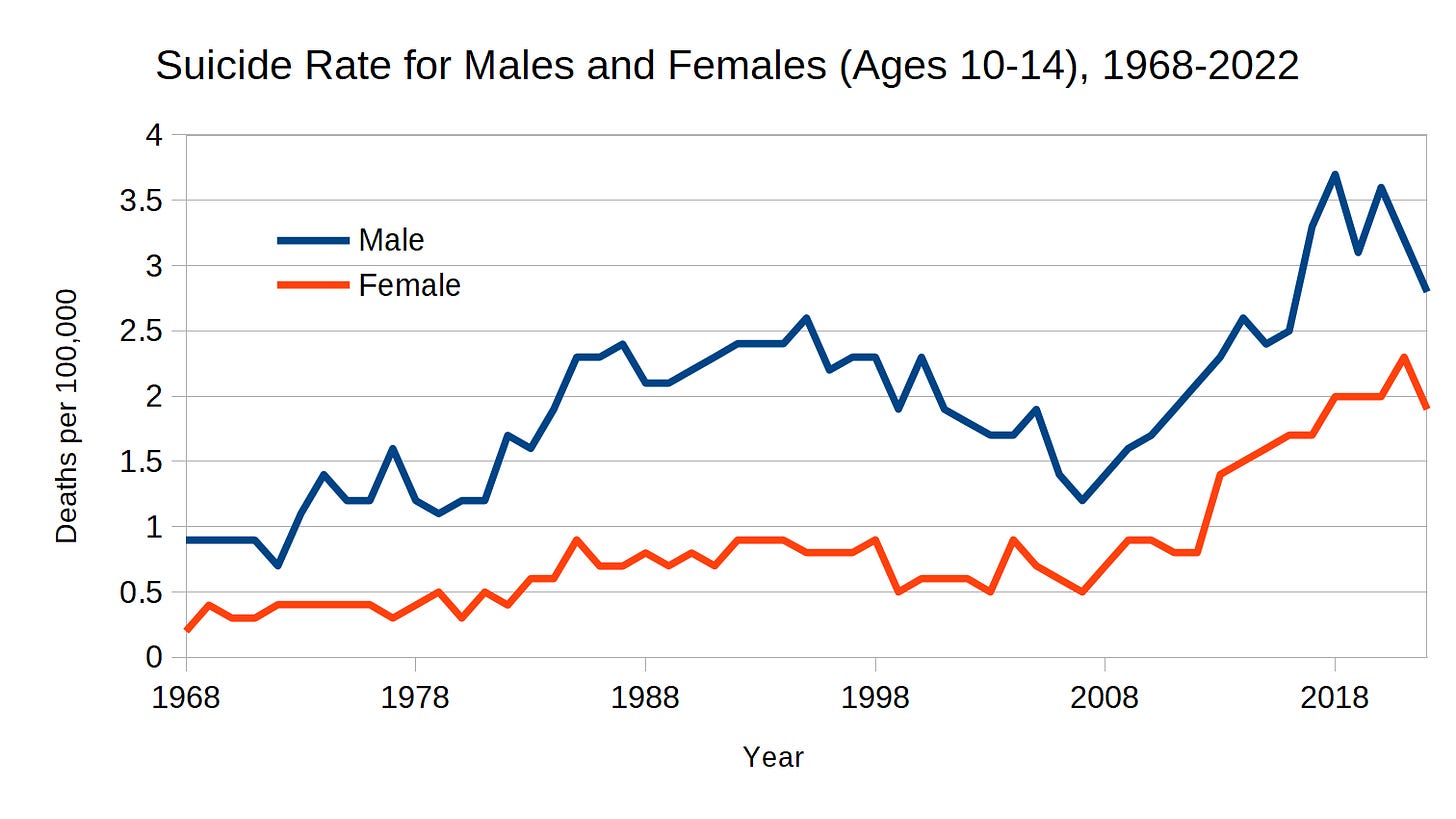

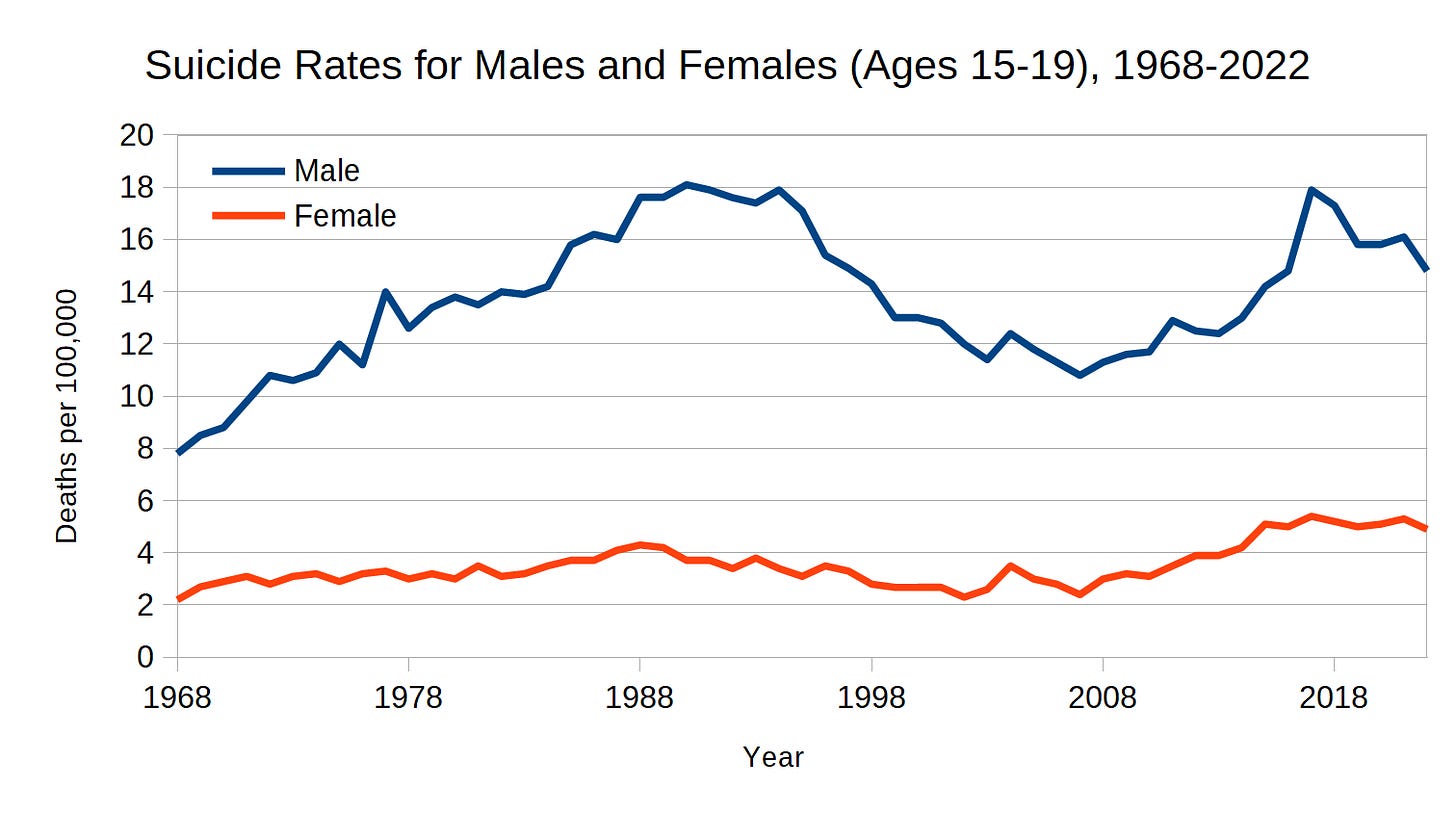

Peter Gray posed three questions to his blog readers about the suicide rates of boys and girls over the past 70 years, focusing on the data in Figure 11. Below are his questions, followed by my answers. Later in this post, I provide reasoning for topics not yet covered.

Question 1:

What was happening between 1950 and 1990 that caused a dramatic and essentially linear increase in suicides for teen boys over this period and a much smaller increase for teen girls?

My answer:

There was a large increase in the money supply beginning in the 1950s, leading to an increase in prices. This affected boys more than girls because there were higher economic expectations for boys.

Question 2:

What was happening between 1990 and 2002 that caused a dramatic decline in suicides for teen boys and a much smaller decline for teen girls?

My answer:

The growth rate of the money supply began to decrease in the 1980s, which slowed the increase in prices. This lessened the pressure on young people. Girls experienced a smaller decline in the suicide rate because economic expectations for them were growing.

Question 3:

What was happening between 2010 and 2018 that caused a dramatic increase in suicides for teen boys and a smaller but still substantial increase for teen girls?

My answer:

The Great Recession was the result of years of money supply growth. After 2009, income and savings failed to support living standards. The dramatic increase in suicide among boys is due to the continued high economic expectations placed on them. The substantial increase in suicide among girls is because economic expectations for them continued to grow.

How Economics Changed Parenting

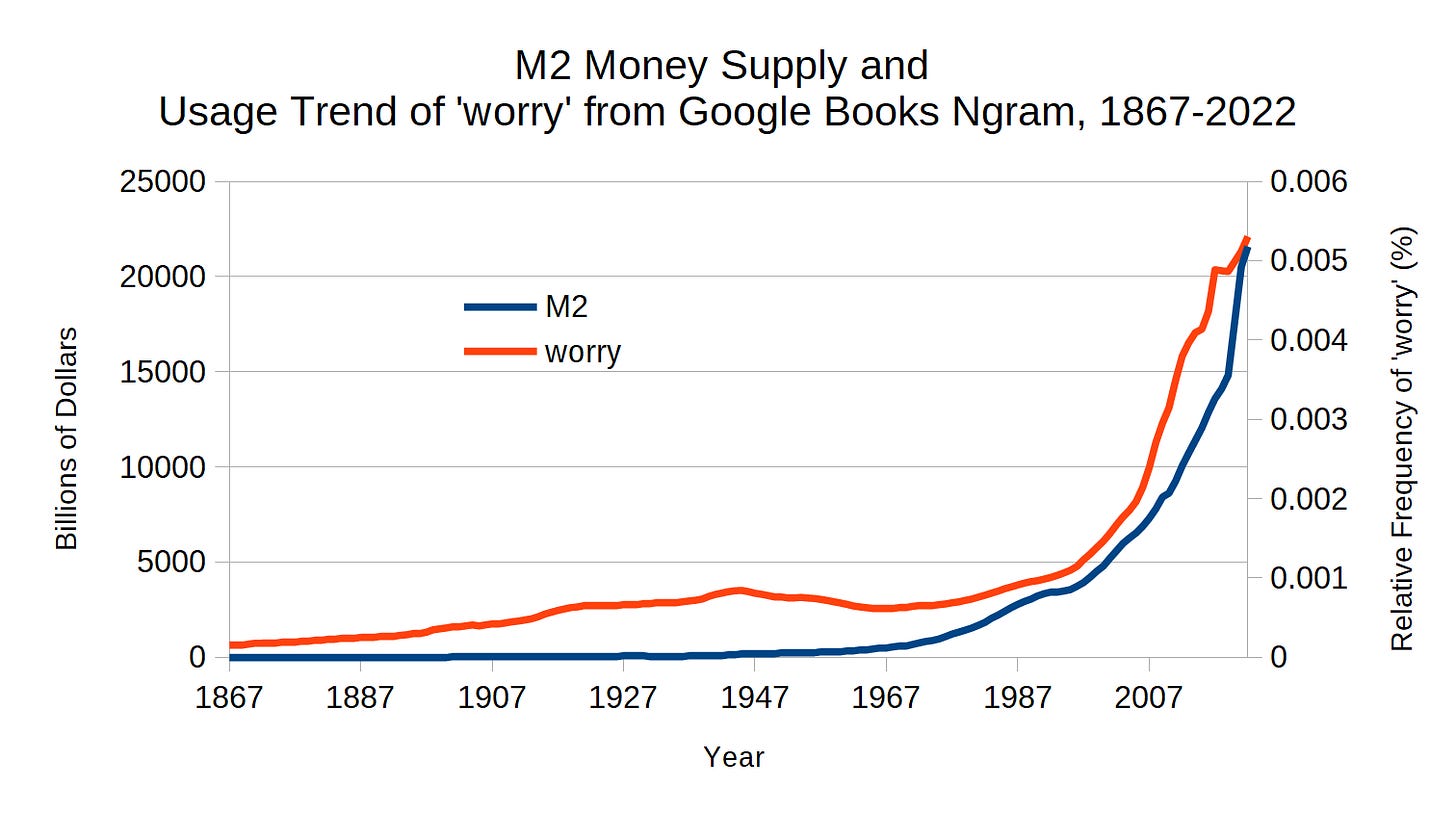

To gain insight into societal trends, we will use Google Books Ngram to examine language patterns. Figure 12 shows that as the M2 money supply has increased, so too has emotional distress in society, as indicated by the rising use of the word “worry.” The effects of a growing money supply are cumulative; as long as the money supply continues to grow, so will easy money-induced distress. Our burden only gets heavier.

The growing sense of worry has led parents to focus more intensely on preparing their children for an increasingly precarious economy. To weather economic storms, securing a good job is seen as essential, and that journey begins by becoming a good student.

The training program in the burden bag metaphor, which was meant to prepare children to carry their own burdens, represents schooling. Just like building physical strength to carry a heavy load, schooling is framed as an essential process to prepare young people for the challenges of adult life. However, the pressures to succeed academically often result in children feeling overwhelmed, just as if they are constantly training to bear an impossible weight.

A study by Nomaguchi and Milkie (2019) (N&M) analyzed the effects of the economy on parenting:

U.S. research has shown that, since the 1990s, arguably as a response to the rise of a college premium, parents have increasingly adopted a parenting style often called “intensive parenting,” pushing their children to work hard in school and extracurricular activities to build their talents, skills, and resumes from a young age to ensure children’s positioning in a competitive global marketplace (Lareau 2003; Milkie and Warner 2014; Nelson 2010; Putnam 2015). These studies indicate that the value of hard work for children among Americans may have increased in the past three decades.

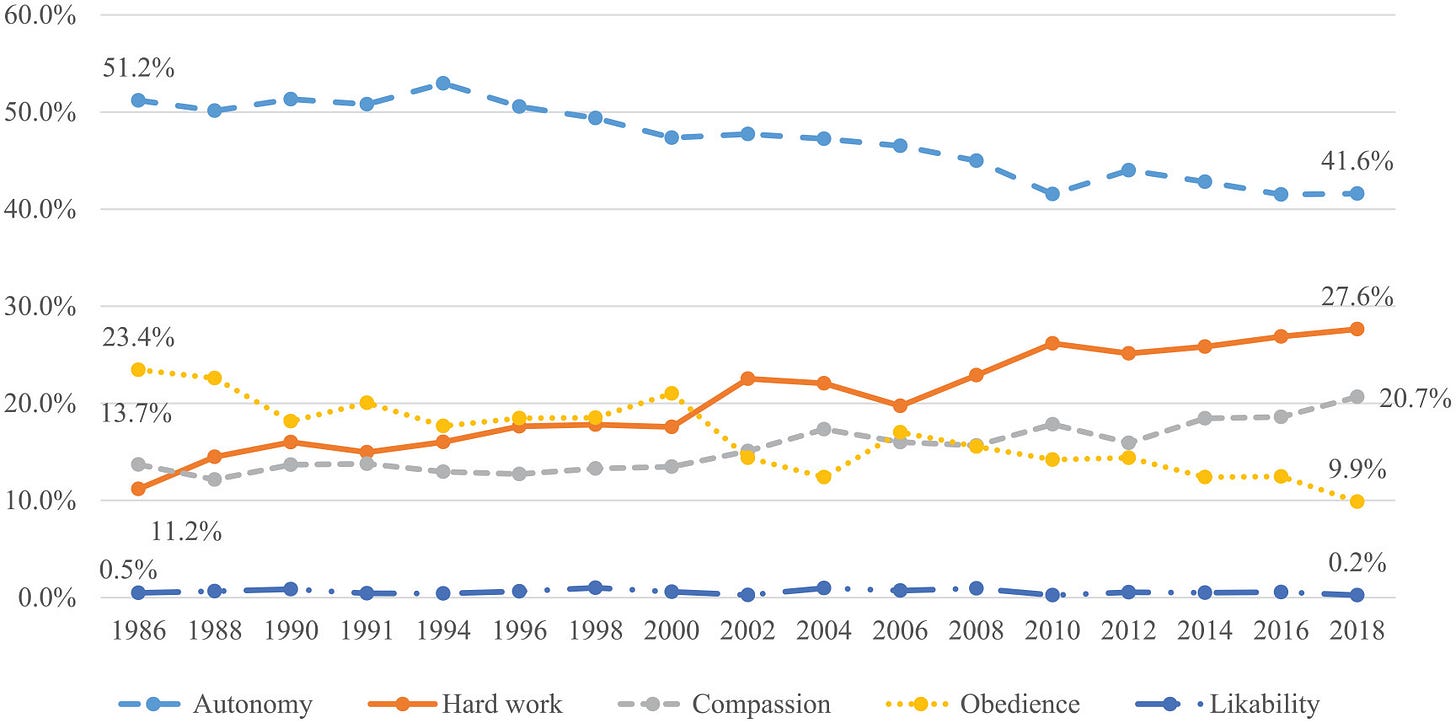

Since 1986, the General Social Survey has asked people to rank five traits important for children to learn:

obedience (“to obey”), autonomy (“to think for oneself”), diligence (“to work hard”), compassion (“to help others”), and likability (“to be popular”)

Figure 13 shows that the desire for autonomy has been decreasing, while the desire for hard work has been increasing:

N&M offered a possible rationale for the shift in values:

The increase in Americans who rank hard work as a more important trait than autonomy for children to learn to prepare them for “life” may reflect a heightened perception of economic insecurity and the need for individual efforts for paving one’s way, presumably economically (Cooper 2014; Nelson 2010)—a retreat to survivalist values in an insecure world. Much research has noted that today’s parenting culture emphasizes parents’ efforts to push children to work hard academically and in developing talents for their futures (Lareau 2003; Milkie and Warner 2014). Though the question asks about what is important for children’s future lives in general, the perceived instability of the workplace and competitiveness in educational institutions are likely relevant factors to imagining what children need for success.

N&M have coined a term for what they have observed, known as the precarity thesis:

The precarity thesis emphasizes that since the mid-1980s, as uncertainties about economic security have risen, Americans’ values for children may have shifted away from self-expression values, like autonomy and compassion, to survival values, such as hard work.

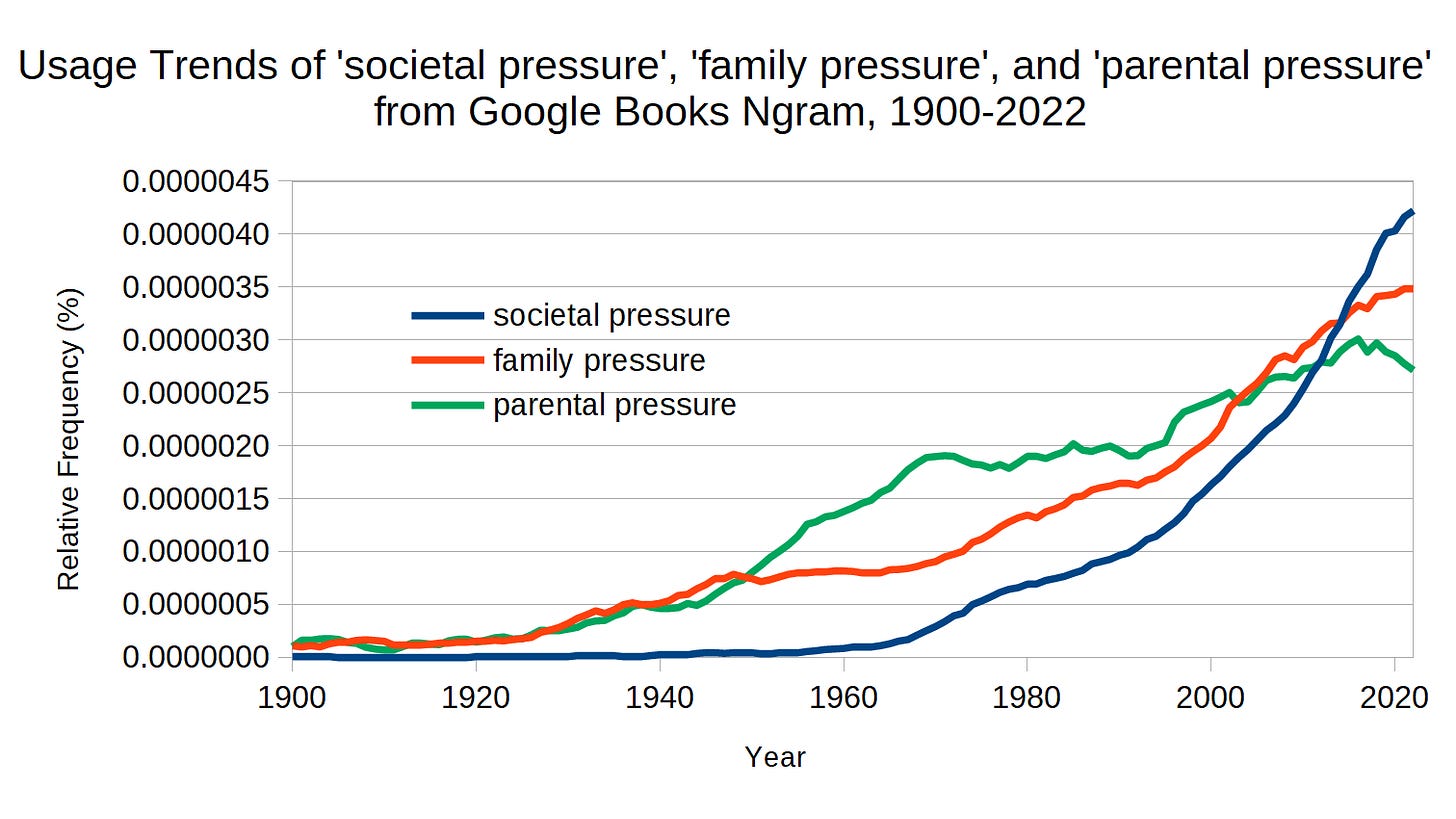

As mentioned above, the data used by N&M started in the mid-1980s, but I suspect that if we were able to obtain data from further back, we would get an even better picture. For example, the usage of the phrases “societal pressure,” “family pressure,” and “parental pressure” have been on the rise for a long time, as shown in Figure 14.

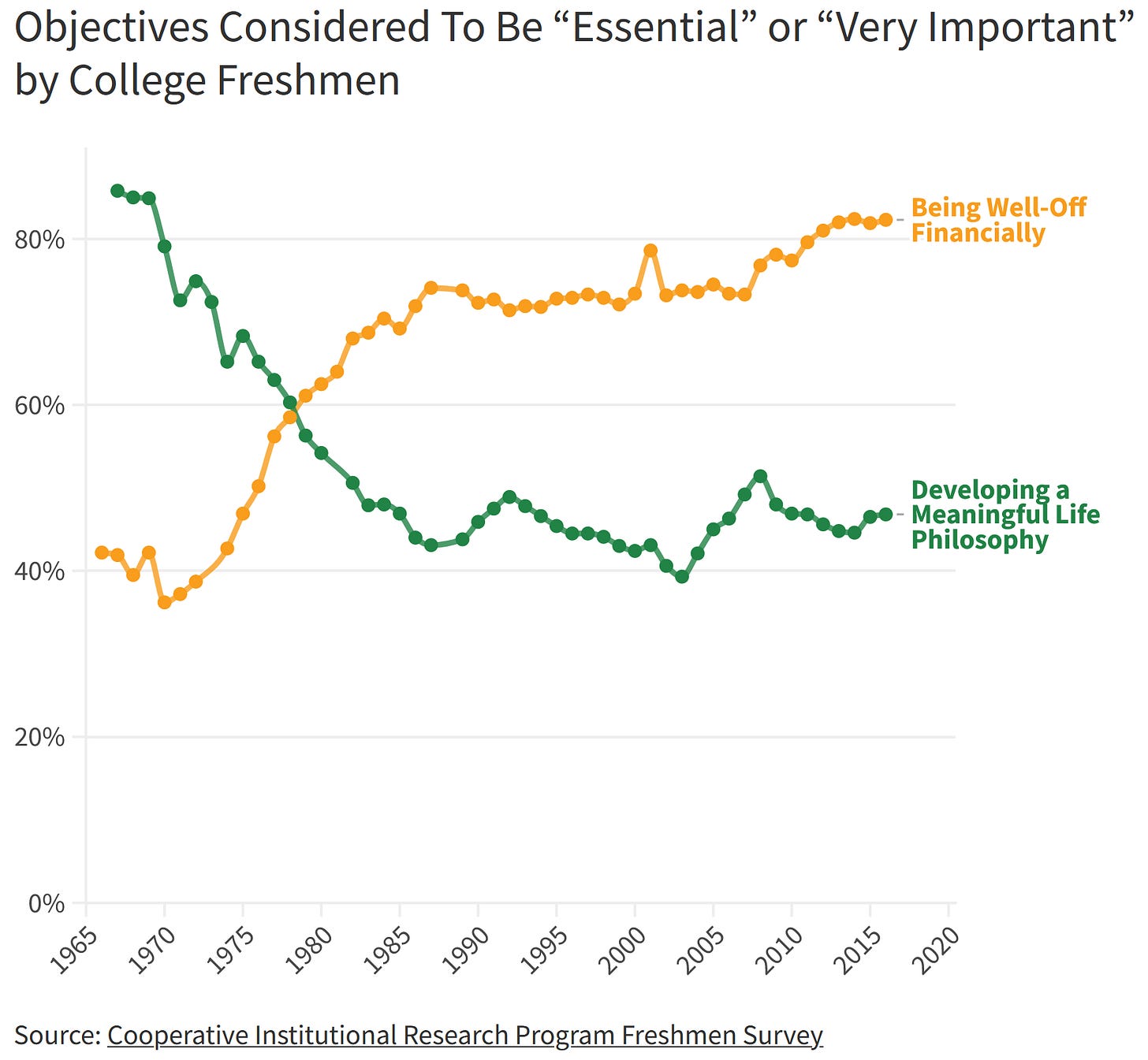

Results from a survey of college freshmen support my suspicions. Figure 15 demonstrates that the transition to what N&M call survivalist values has been underway since at least the late 1960s. According to the Cooperative Institutional Research Program Freshmen Survey, the priority of “Being Well-Off Financially” steadily increased in the 1970s, overtaking “Developing a Meaningful Life Philosophy” around 1979. Since then, financial well-being has remained more important for college freshmen, while the importance of developing a meaningful life philosophy has gradually declined and fluctuated.

Academic Stress

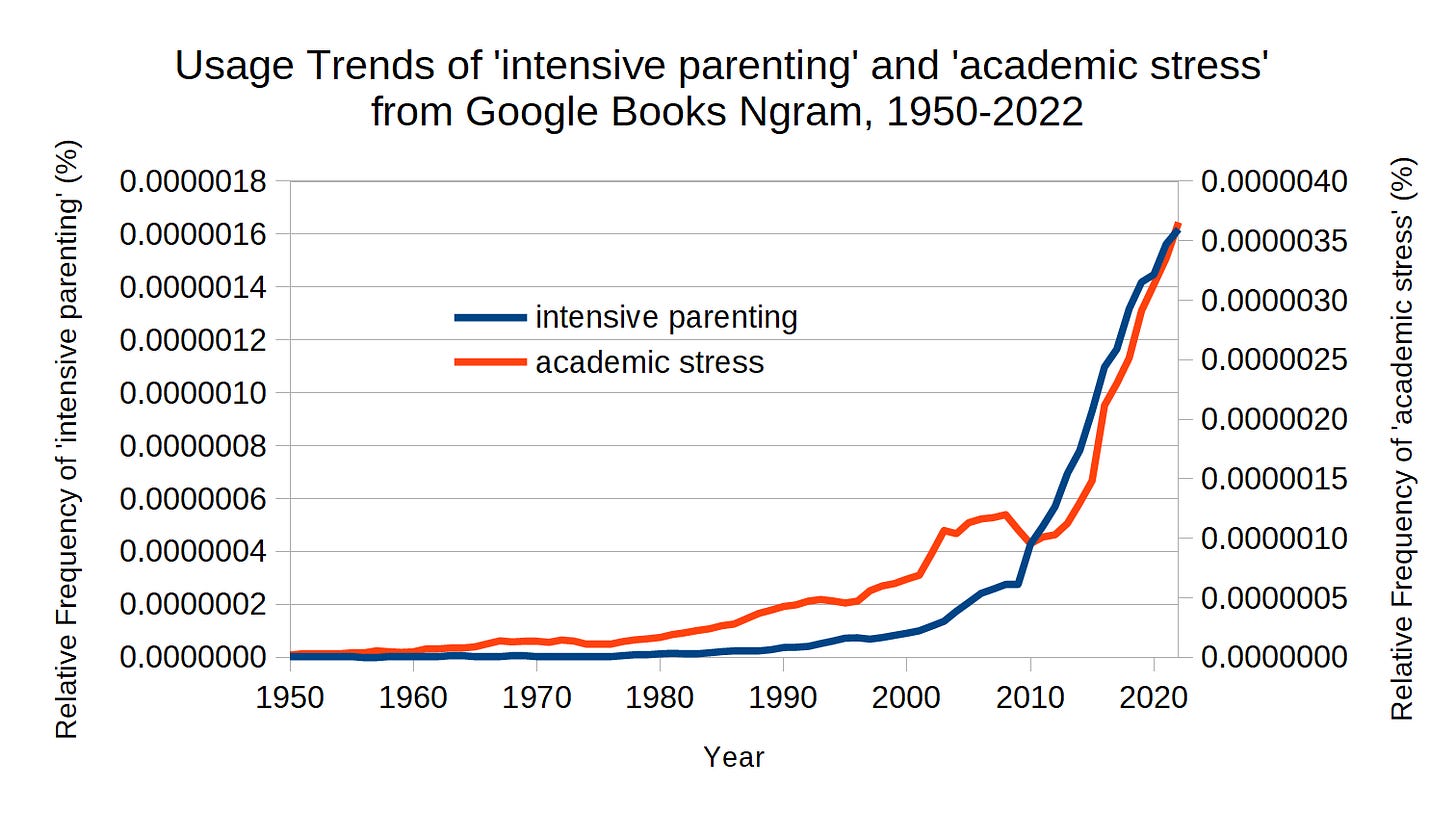

Colorado Public Radio acknowledges that “It’s difficult to track an increase in academic stress,” but adds that “Psychologists and pediatricians have watched it ramp up since 2009.”

N&M’s study found that economic instability and insecurity lead to an increase in intensive parenting, which emphasizes schooling. When considering the Great Recession, Figure 16 supports N&M’s precarity thesis, showing a sharp rise in the use of the phrase “intensive parenting” after 2009, followed by an increase in “academic stress” after 2010.

In this section, we will discuss the relationship between academics and the distress experienced by young people. For simplicity, the focus will be on college students. As the Cleveland Clinic points out, teenagers and college students often face similar stressors.

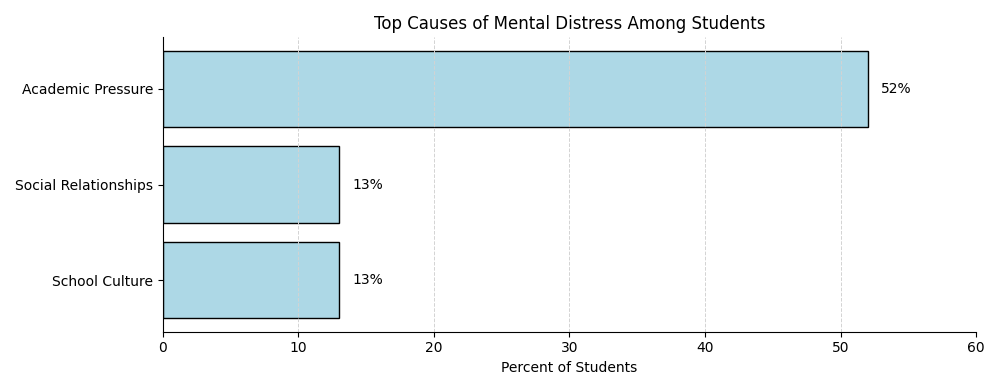

In their book The Real World of College (2022), Howard Gardner and Wendy Fischman investigated mental health distress on college campuses by interviewing students from various schools. Here are their findings relevant to our discussion:

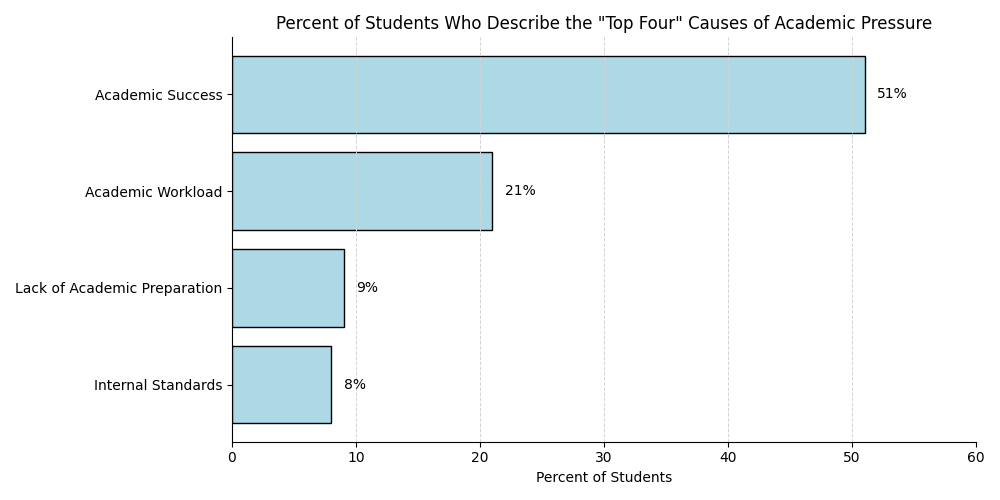

While some hypothesize that students are “overly coddled,” or that social media have caused students to feel more loneliness and social anxiety, the majority of students in our study describe an overwhelming pressure to do well, as opposed to just “do okay”—indeed, to build a perfect resume—as the primary source of mental health distress.

Across all students in our study, the most common explanation (52% of all student-reported causes) about why mental health is the most important problem on campus is academic rigor — the “pressure” of academics.

Perhaps not surprisingly at this moment in history, when students discuss academic pressure as a cause of mental health, the most frequent explanation focuses on achieving external measures of success—securing a high grade-point average, or “doing well” on an assignment or an exam (51%).

Interestingly and importantly, these concerns with the external markers of success are the most common descriptors for academic rigor at every campus – from most to least selective.

Figure 17 shows that academic pressure is the largest contributing factor to mental health distress among college students.

Figure 18 highlights that the primary source of academic pressure for college students is not the workload itself but, as Gardner and Fischman mentioned, the emphasis on “achieving external measures of success.”

When The Harvard Crimson examined the stressed and busy lives of today’s college students, they consulted Wendy Fischman for commentary:

Modern students are “so transactional about their college experiences, so focused on building their own resumes, building a profile, having experiences that’ll lead to a job,” Fischman said.

Fischman’s research demonstrated that students’ extracurricular involvements were usually “more about collecting activities that they could put on their resume — much less about exploration and trying to discover real interests and passions,” she said.

Fischman noted that students repeatedly referenced a desire to be perfect, contributing to stress that occurs “daily, if not on the minute.”

Grade Inflation

Grades seem to serve as a proxy for external pressures, such as parental expectations. In their book Cheating In College (2012), McCabe et al. elaborate on how the pressure to achieve good grades contributes to grade inflation:

Students also may feel free to do what ever it takes to get the job done and get the grade desired in the time allotted, and they will determine how much time they have to allot to their academic obligations, after their other activities are complete— social, athletic, relaxation, and so on. And, of course, getting the grades they feel they need in order to get into their first-choice college and satisfy their parents’ expectations appears to be a major motivator. Unfortunately, in our view, many students have transferred this pressure to their teachers, in high school and in college, putting upward pressure on individual grades and overall grade distributions. As more faculty members have given in to such pressure, often to avoid the hassle of dealing with parents who feel their high school children deserve better grades, the collective result seems to have been grade inflation.

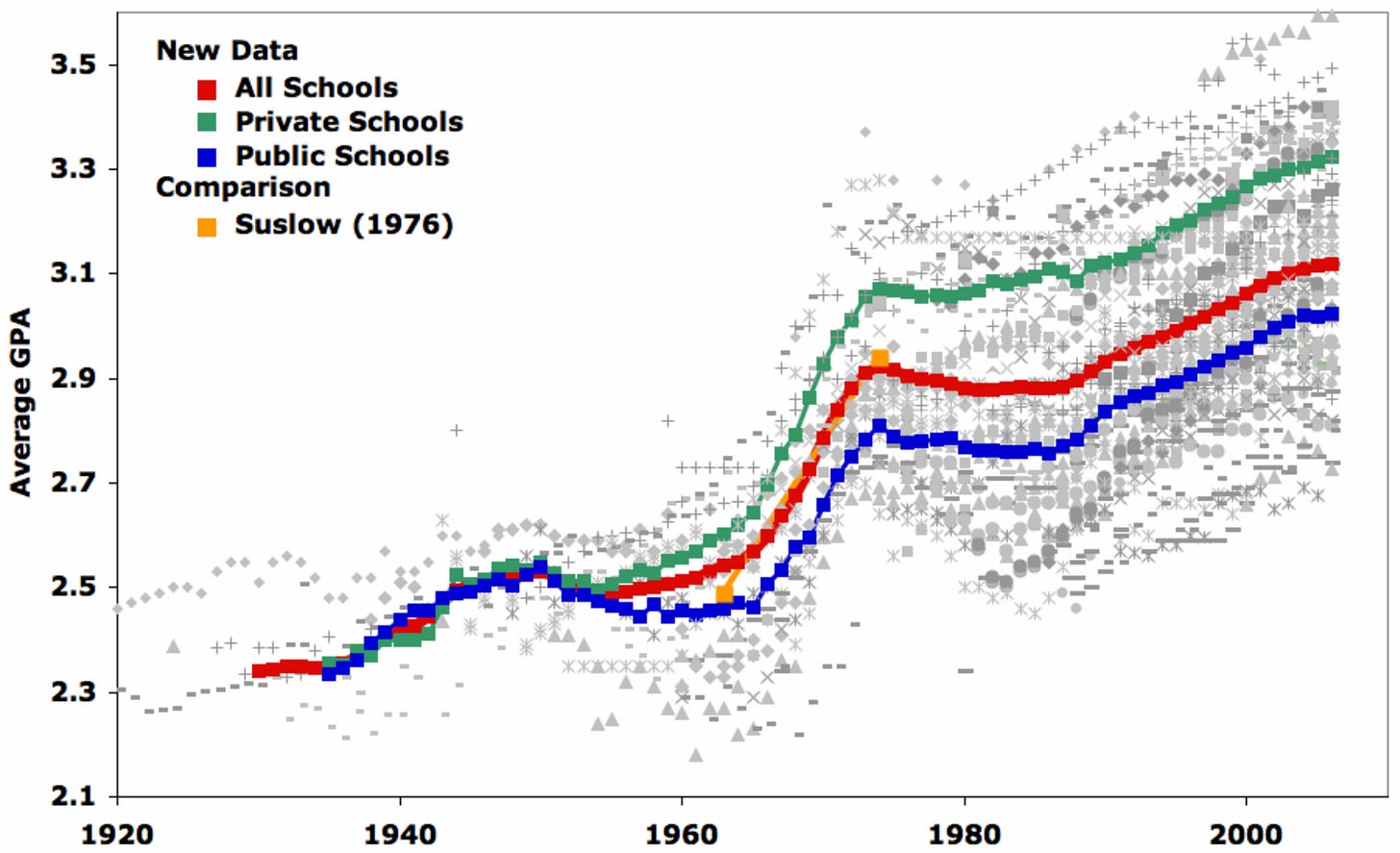

Figure 19 illustrates the trends in average GPA at American colleges from 1930 to 2006. Individual schools are represented by gray data points, while the colored squares represent the average GPA for three categories: private schools (green), public schools (blue), and all schools combined (red). The orange squares correspond to Suslow’s 1976 data on college grades, which serves as a comparison. The graph reveals a general upward trend in GPA, signifying grade inflation across all types of institutions. Notably, private schools consistently exhibit higher average GPAs compared to public schools, especially from the 1960s onward.

A study by Swartz et al. found that trying to combat grade inflation might end up hurting students. Quartz presented the study’s findings:

If you go to a college with tougher grading standards than average, you’re less likely to get into graduate school, new research shows—and there’s a similar problem within the job market. Correspondence bias, a psychological phenomenon that makes us judge people based on their behavior (like GPA) while ignoring context (like the difficulty of the school attended), could be keeping you from getting the jobs you want.

Another article from Quartz reported how Princeton University, from 2004 to 2014, tried to fight grade inflation and lost. During Princeton’s war on grade inflation, a 2013 Atlantic article described the results:

the lower GPAs resulting from the grade deflation policy have had a slightly negative impact on job and graduate school prospects. In 2009, Princeton began to provide a notice with its transcripts that explain the deflation policy, but that likely has little impact.

Harvard Students

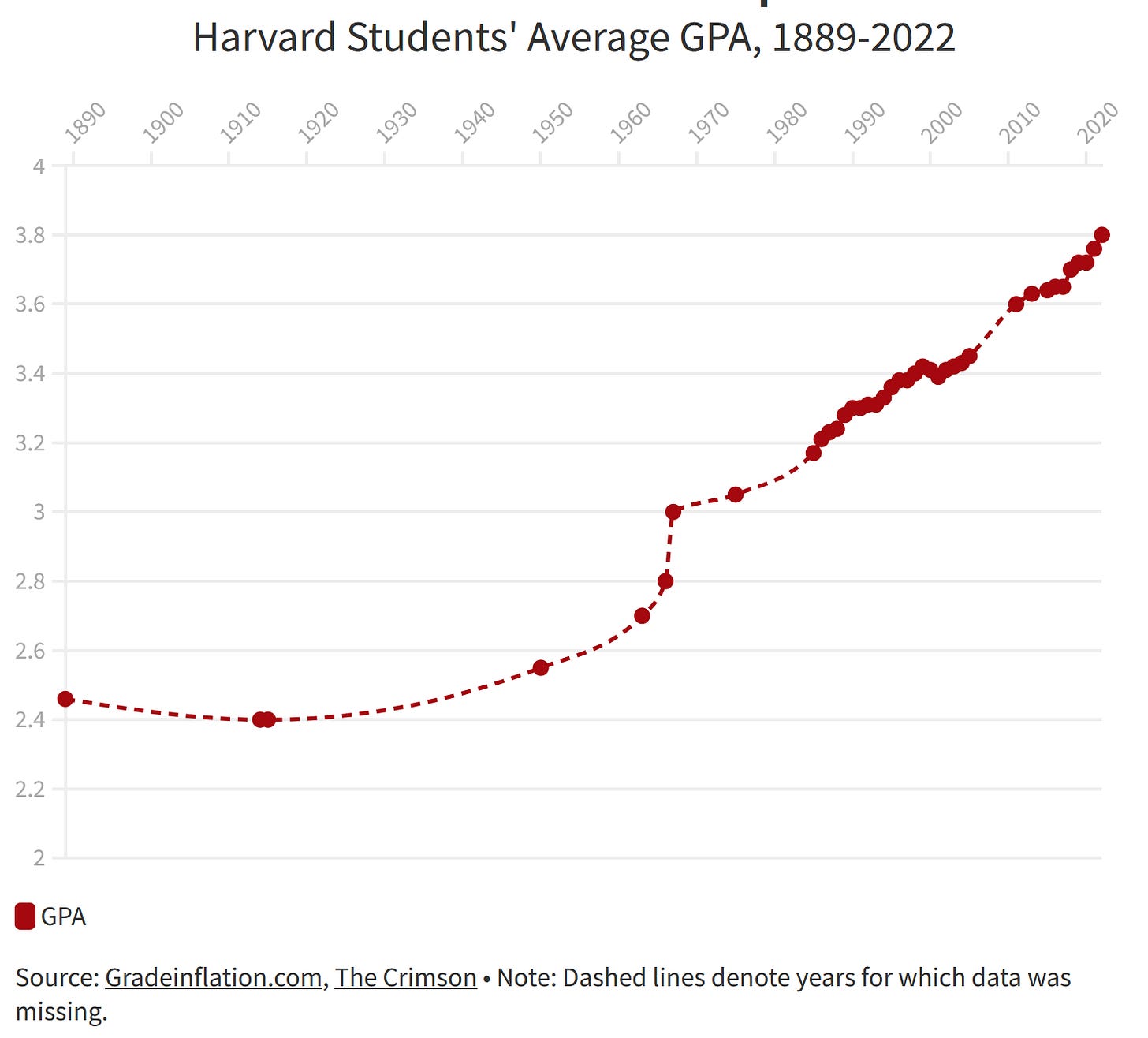

Harvard University is known for grade inflation. Figure 20 shows the average GPA of Harvard students from 1889 to 2022. Similar to the general trend in college GPAs shown in Figure 19, Harvard’s average GPA remained relatively stable between 2.4 and 2.6 until the 1960s, after which it steadily increased to approximately 3.8 by 2022.

Complaints about Harvard’s grade inflation date back to at least the late 19th century, yet those who complain often overlook the intense pressure faced by students. The following excerpts from an op-ed in The Harvard Crimson by Sami E. Turner, which includes quotes from Professor James T. Engell and former Dean Thomas A. Dingman, illustrate how Harvard students have adopted N&M’s survivalist values:

In a 1966 booklet called “College Admissions and the Public Interest,” B. Alden Thresher, the first ever director of admissions at MIT, laid out two approaches to higher education: the “poetic” and the “utilitarian.” While “utilitarian” students were “impelled by practical considerations,” their “poetic” counterparts took “innate pleasure” in learning.

By the time students get to Harvard…academics are often the least of their concerns. Instead, some view college as “a stepping stone rather than an end in itself,” as Engell put it.

The clearest example of Harvard’s careerist turn is its extracurriculars. Instead of being a way to “chill” or “get away from the academic stressors,” as Dingman says clubs used to be, student organizations — such as Harvard College Consulting Group and Harvard Financial Analysts Club — increasingly function as pre-professional outlets.

These efforts often come at the expense of classwork, converting even the most poetic student into a utilitarian careerist.

Research shows a long-term, national decline in hours devoted to schoolwork per week by college students. Here, too, Harvard seniors reported spending almost as much time collectively on extracurriculars, athletics, and employment as they spend on their classes. This stands in stark contrast to students’ old priorities.

Now, students are “more conservative in course choices,” according to Dingman. Risk-averse careerism has seeped into the choice of classes themselves. Many students now concentrate in fields like Economics or Computer Science to increase their job prospects. Their grades, too, have assumed an outsized importance due to increasingly competitive graduate school applications, according to Engell.

I’ve seen it: My pre-law friend dropped out of a class after receiving a B+ on an essay, for fear of rejection from law school.

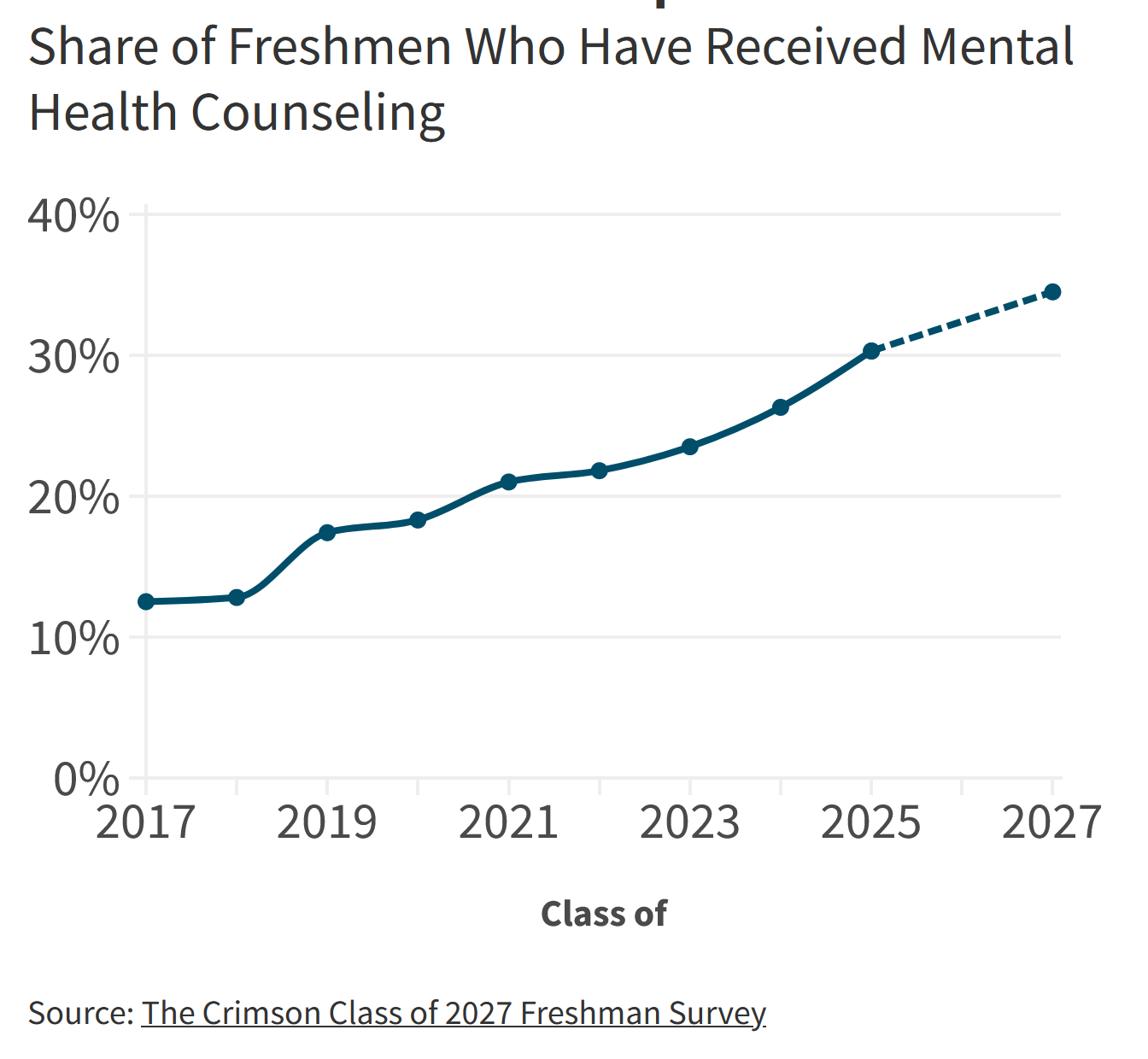

The pressure Harvard students face appears to be reflected in the rising share of freshmen who have received mental health counseling, as shown in Figure 21. For the Class of 2017, just over 10% of freshmen reported using mental health services, and this proportion has steadily increased, reaching nearly 35% for the Class of 2027.

The pressure faced by Harvard students also appears to be reflected in concerning suicide statistics. According to The Daily Beast:

Harvard has said the school’s suicide rate is about 5 per year for 100,000 students. But the Crimson has disputed this figure, estimating it at 18.18 per 100,000, or as much as 24.24, if students taking leaves of absence are included. The national average for college-age suicides (18 to 25 years old) is 6.18, according to a survey out of University of Virginia.

Perfectionism in Young People

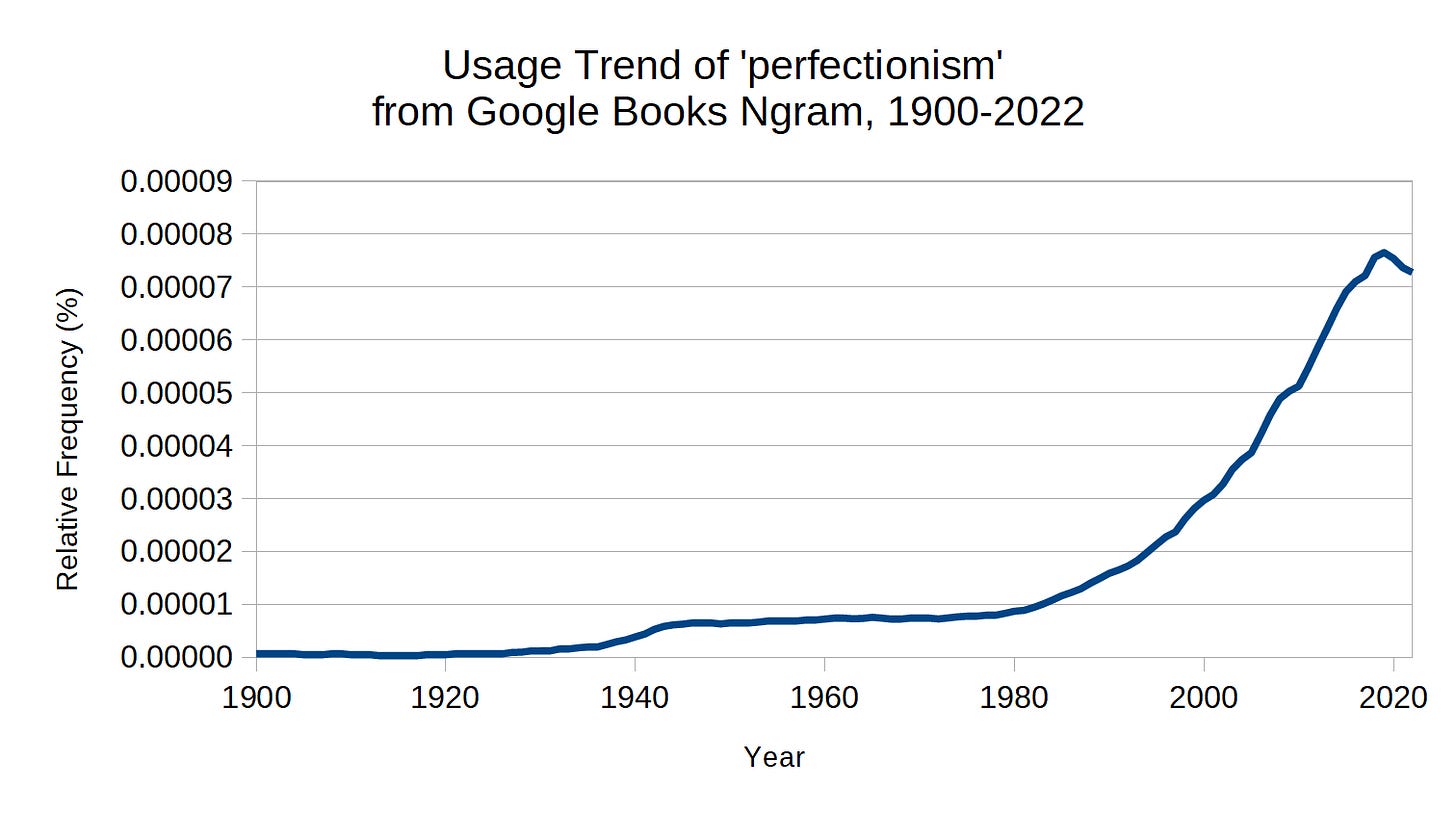

Unrealistic expectations have been increasing. To get a general sense, Figure 22 shows the growing use of the word “perfectionism.”

A 2018 Washington Post article reviewed a study about the rise in perfectionism among college students between 1989 and 2017:

A new study called “Perfectionism Is Increasing Over Time” finds that young people are more burdened than ever by pressure from others, and that includes parents. Psychologists Thomas Curran and Andrew Hill found that unhealthy perfectionism has surged among young adults, with the biggest increase seen in those who feel pressured by the expectations of others. Perfectionism, the study’s authors say, is a mix of excessively high personal standards (“I have to excel at everything I do”) and intense self-criticism (“I’m a complete failure if I fall short”). In its unhealthiest forms, perfectionism can lead to eating disorders, depression, high blood pressure and thoughts of suicide.

In a 2022 study, Curran and Hill conclude that “increases in parental expectations and parental criticism offer the most plausible explanation for rising perfectionism to date.”

Curran and Hill emphasize that parents are responding to economic instability and insecurity:

If it is the case that changing parenting practices are linked to rising perfectionism, we feel it important in closing to restate our conviction that parents are not to blame.

Against a background of downward mobility, in economies where the next generation will be materially poorer, and where inequalities are gaping and exacerbated by escalating returns to elite college education, rising parental expectations and criticism are rational, indeed inevitable, and are deployed in what is understood to be the best interests of the child given the competitive and lopsided society they happen to inhabit.

Expectations and Suicide

Francine Klagsbrun, in her book Too Young To Die (1984), describes how parental expectations are harming teens:

In a society that measures success in terms of wealth and power, they feel great pressure to do well in school, get good jobs or enter the “right” professions, and to accumulate money and status. The “American Fairy-Tale” is the label psychiatrist Darold A. Treffert applies to the unreal expectations parents have of their children. For thousands of teenagers the fairy tale ends in drug addiction, alcoholism, mental illness, and suicide.

Klagsbrun shows how parental pressure prevents college students from engaging in meaningful conversations with their parents:

The pressures that make up the American Fairy-Tale have contributed to the rise in suicides among the young, and especially to spiraling suicide rates among ‘college students. Suicide is the second cause of death for college students, and the rate of suicide among them is higher than it is for other young men women of the same ages. Although pressure to achieve high grades and success is not the only factor leading to college suicides, it is an important one. Suicidal college students interviewed by psychologists spoke about their inability to discuss frustrations or failures with their parents. So imbued were the parents with their own fantasies of success and achievement for their children that they simply did not want to hear about the fears or self-doubts the students had. Many of the suicidal students worried constantly about doing well in school.

In their book Youth Suicide (1986), Brent Q. Hafen and Kathryn J. Frandsen explain why parents put so much pressure on their children:

In a significant number of teenage suicides, the parents had placed a massive amount of pressure on the child to “measure up” to certain standards. While many — if not most — parents pressure their children to succeed, in the suicides it seemed that the parental pressure stemmed from the parent’s own feelings of failure, insecurity, and inadequacy. The child learns quickly that the only way he can win approval from his parents is to “perform” in the desired channels.

The Pressure on Girls

Holinger et al. made a prediction about the female suicide rate in their 1994 book Suicide and Homicide among Adolescents:

We suggest that even to this date, the culture’s expectations for the male (in ancient times, the hunter or gatherer) differ from those for the female (in ancient times, the caretaker). In this sense, both the poor African-American adolescent male and his white middle-class male peer who die a violent death are those who on some level believe that they cannot, for whatever reason, fulfill the role expected of them. This can also be seen as a failure of the social order, in that it does not present enough flexibility to its youth as they grow up and attempt to find a place within the society. The adolescent female, despite the considerable pressure that has been placed on her in the United States in the last decade, still has more options than boys as she grows up to adulthood. Therefore, she may not be as desperate as often as her male peer—and hence the female suicide and homicide rates are considerably lower than the male rates. It is our prediction, however, that as women become truly equal to men in the labor force, with expectations similar to those for men, the rates of suicide and homicide for females will become more like those of men.

As we will discuss in this section, rising expectations for girls can help explain why The Gap Between Male and Female Youth Suicide Rates is Narrowing in the US, as shown in Figures 23 and 24.

In her book Enough As She Is (2018), Rachel Simmons explains how our expectations are harming girls:

Why are girls struggling? Psychologists call it “role overload”—too many roles for a single individual to play—and “role conflict”—when the obligations of the roles you play are at odds with one another. Both conditions are known to induce high levels of stress. In the so-called age of Girl Power, we have failed to cut loose our most retrograde standards of female success and replace them with something more progressive. Instead, we’ve shoveled more and more expectation onto the already robust pile of qualities we expect girls to possess.

“Women today have to succeed by traditionally male standards of education and career, but they also have to succeed by the traditionally female standards of beauty (not to mention motherhood),” Duke University’s Susan Roth has written. Girls have to be superhuman: ambitious, smart and driven, physically fit, pretty and sexy, socially active, athletic, and kind and liked by everyone. As Courtney Martin put it in Perfect Girls, Starving Daughters, “Girls grew up hearing they could be anything, but heard they had to be everything.”

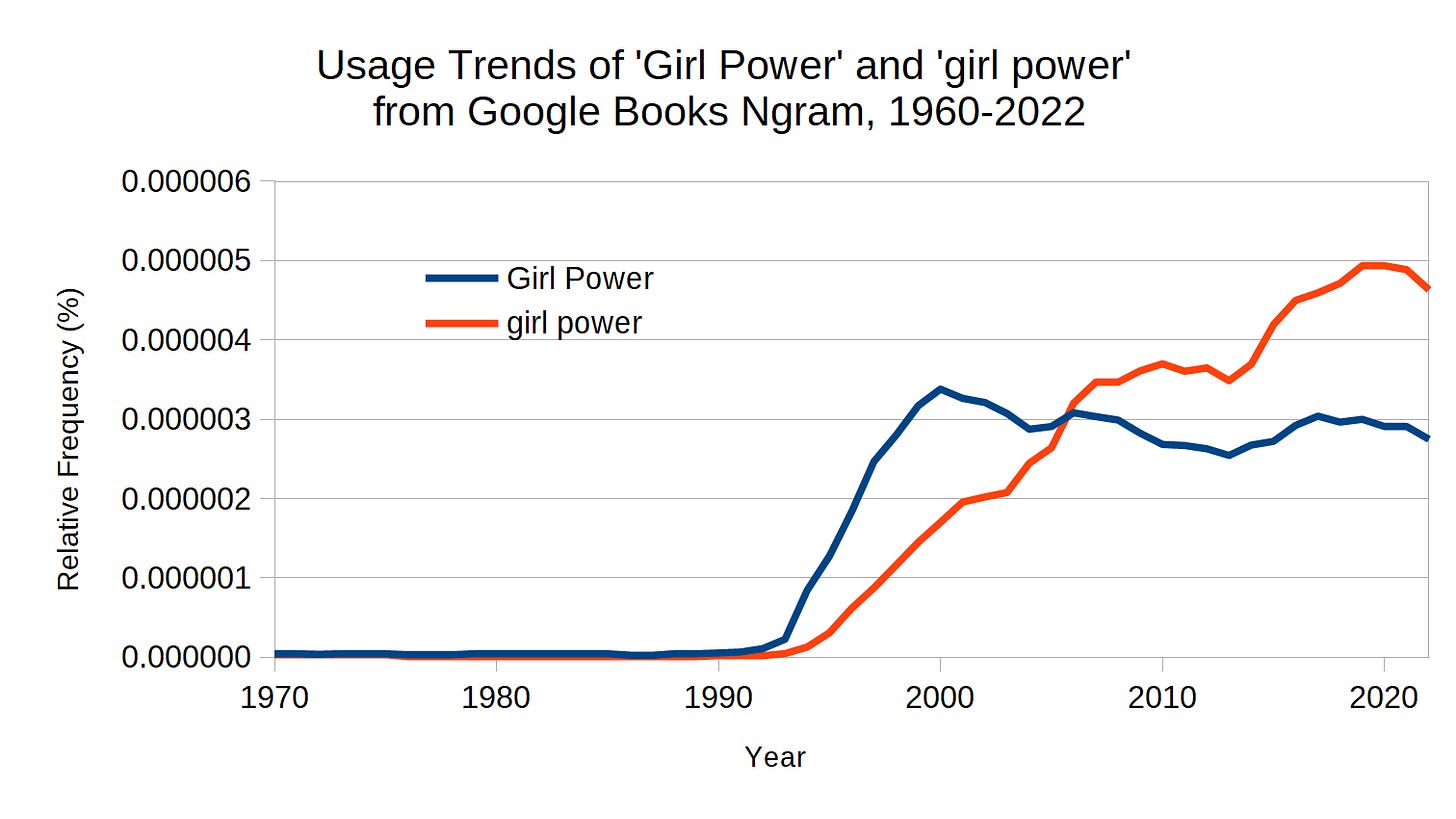

As Simmons mentioned, the age of Girl Power has increased the expectations for girls. Figure 25 shows that the phrases “Girl Power” and “girl power” became popular in the 1990s, providing context for the findings in the following Economist article.

The Economist (2020) shows how much girls’ priorities have changed:

In 1972 a group of working-class girls in Ealing, London, were asked to rank their life priorities. They ticked love, a husband and a career in that order. When the same survey was repeated in 1994 the outcome had more or less reversed. We asked the girls we talked with to rank their priorities for the future on a form. “Interesting job”, “Change the world” and “Financial independence” were reliably found near the top. “Love” was in the middle; “Marriage”, “Get rich” and “Have children” were low—and sometimes crossed out.

The same Economist article also acknowledges the pressure girls are under:

When you ask girls what makes them anxious, many indeed mention pressure: pressure to do good, look good and be good.

When it comes to balancing growing economic expectations with being a girl, a study by Campbell et al. (2021) notes:

Previous research indicates that stress and educational pressure is particularly correlated with worse mental health in adolescent girls (Schraedley et al., 1999; Wiklund et al., 2012). Indeed, changing norms of female education and economic participation can increase educational stress and psychological distress for girls whilst they are still burdened with traditional anxieties related to maintaining a female identity and appearance (West & Sweeting, 2003).

A review by Steniford et al. (2021) found that girls from various backgrounds face pressures from their families:

There was evidence in the studies that girls from middle/upper-class backgrounds often felt pressures to “live up to” their parents’ standards and to emulate their successful careers and lifestyles (e.g. Eriksen, 2021; Spencer et al., 2018). In contrast, Jackson (2010) found that the lower/middle-class students in her UK study felt that their parents wanted them to do better than themselves so that they might have brighter futures; “[My parents] want me to do well. They want me to get where I’m going ‘cause they said that they wish they’d done well at school and done better…” Jane, working-class student (pp. 45–6). Some studies further detailed how lower/middle-class girls felt under pressure to do better than unsuccessful siblings or match a sibling’s high performance (e.g. Jackson, 2010; Låftman et al., 2013).

Academics and Psychological Needs

In this section, we will explore how schooling contributes to increased screen time.

Peter Gray points out how child labor still continues to this day but in a different form:

Because of child labor laws, children today don’t labor long hours for wages, but now they labor long hours at what we call “education.”

Psychologists Berney Wilkinson and Richard Marshall discussed on their podcast the negative consequences of making academics the primary focus of children’s lives. Here is their exchange (with minor edits for readability):

Wilkinson: Our focus, if we think about the development that we’re typically focusing on, is academics. Right? We want them to make all A’s — this is our goal as their parents…We want them to be able to go to a good college…

So, while they may be building some of these academic skills, remember that as you’re growing significantly in one area of development, other areas of development may remain somewhat stagnant or don’t change as much. And so, while they’re building those skills, these other skills — social, emotional types of things, taking some responsibility, building their own sense of self-worth, and developing their own self-confidence — are not progressing the way that they should.

Marshall: That’s right. If you’re a parent…what is your objective? You know, we have many parents who come in here, and they’ll say, “Well, her job is just to go to school.”

Nir Eyal, in Indistractable, explains the unintended consequences of making academics the sole measure of competence for young people:

[Richard] Ryan warns, “We’re giving messages of ‘you’re not competent at what you’re doing at school,’ to so many kids.”

If a child isn’t doing well in school and doesn’t get the necessary individualized support, they start to believe that achieving competence is impossible, so they stop trying. In the absence of competency in the classroom, kids turn to other outlets to experience the feeling of growth and development. Companies making games, apps, and other potential distractions are happy to fill that void by selling ready-made solutions for the “psychological nutrients” kids lack.

Eyal discusses the challenges faced by students who aren’t doing well in school, but I suspect that high-achieving students could be negatively affected as well. As Wilkinson and Marshall pointed out, areas such as social and emotional development don’t mature properly when academics are treated as the sole focus for young people. Even students who excel academically may do so at the expense of these other areas, as their time and energy are focused solely on academic pursuits. This aligns with Deci and Ryan’s need density hypothesis, suggesting that the pursuit of academic excellence can sometimes come at the cost of fulfilling essential psychological needs. Many teens may lack autonomy due to strict parental control, struggle with competence under unrealistic academic expectations, and feel disconnected from others because they are on a path chosen for them, where their values don’t align with those around them. In response, these students often turn to screens and other distractions as a way to cope with the pressures they face.

This dynamic could explain what happened with Abby. In a different part of her NPR interview, she explained (with minor edits for readability):

Sometimes, it actually helps because, when you’re really upset, you can use your phone to distract yourself, or contact a friend who can help you, or you can just use it to get your mind off of the bad thoughts.

The Youth Mental Health Crisis and Screen Time

When it comes to the youth mental health crisis, the animosity towards social media is misplaced.

Screen time is an anodyne.

The real solution is to create a world where people do not feel the need to escape.

Before I close, I want to clarify my stance on screen time. Like anything else, anodynes—including screen time—can become harmful if misused. However, the solution is not a top-down, one-size-fits-all approach like prohibition. Anodyne abuse is a symptom of disempowerment, which is why its usage tends to increase during times of distress, such as economic insecurity and instability. The real solution lies in empowering individuals to take control of their lives.

The youth mental health crisis is multifaceted, involving economic, social, and psychological elements. By understanding the broader context, we can move beyond simplistic blame and attempts to control to a more nuanced approach that is based on compassion and understanding of young people’s needs. In my future posts, I will continue to explore these themes further and provide solutions.

How Strong is My Theory?

My theory can explain everything that SSMT can, and more. It accounts for both teen suicide and homicide rates among boys and girls in the current youth mental health crisis and the previous one that peaked in the 1990s.

There are many other negative effects of economic instability and insecurity caused by easy money policies that I could have explored. However, for simplicity, I focused on one key aspect of our current crisis: how these conditions create an environment where parents feel pressured to push their children into intense academic paths, prioritizing success over well-being. This pressure takes a toll on teens’ psychological health, resulting in increased distress and distraction.

I acknowledge that my observations are correlational; however, my theory is falsifiable.

The greatest strength of my theory lies in its ability to predict certain trends due to its clear causal mechanism. The primary factor driving changes in the suicide and homicide rates in the United States is the growth of the money supply. Therefore, as time goes on, youth suicide and homicide rates will generally continue to follow M2 growth.

Thanks so much for reading! If you found this post helpful, I’d really appreciate it if you could share it with others. And if you’d like to stay updated, please consider subscribing.

Interesting theory overall. One more thing I would like to add: it is probably more a question not of how much the M2 money increases, but rather WHO does the money go to? Historically, this newly-created easy money went directly to the big banks, a sort of UBI for the rich. So of course the effects will be at least somewhat destabilizing, as it is so lopsided. We all know now that the "trickle-down" theory is BS, so why don't we simply give all newly-created money to We the People instead? That would have to be better IMHO.